Linen comes in a wide range of colors, weaves, and intriguing blends. From top left, plain-weave linen; embroidered lace; crepe; gauze; burlap; embroidered plain weave; rayon/linen gauze; sateen; and various novelty weaves.

Once you get past the inevitable observation that linen wrinkles, you can start assessing its many charms: It’s available in a wide variety of weights, textures, and forms, and in colors ranging from subtle to vivid. It’s attractive even in its natural, undyed state. It’s easy to care for, comfortable to wear, and, nicest of all from the dressmaker’s point of view, shows off almost every sewing and embellishing technique while making them easy to execute because of its crisp, unfussy, and adaptable nature. In fact, linen’s one of the easiest fabrics to sew— and there are ways to reduce the wrinkling. Read on for the whole story, from choosing your linen project to learning the best way to iron and care for it.

Linen comes in a wide range of colors, weaves, and intriguing blends. From top left, plain-weave linen; embroidered lace; crepe; gauze; burlap; embroidered plain weave; rayon/linen gauze; sateen; and various novelty weaves.

Linen comes in a wide range of colors, weaves, and intriguing blends. From top left, plain-weave linen; embroidered lace; crepe; gauze; burlap; embroidered plain weave; rayon/linen gauze; sateen; and various novelty weaves.

Flax, ancient and hi-tech

The flax plant provides the long, lustrous, smooth fibers that have been processed into linen since before the dawn of history. Flax fibers are lint-free (there are no short pieces to work loose), resistant to dirt (their smooth, hard surface repels it), lustrous (thanks to their natural wax content), and two to three times as strong as cotton. The flax fiber has a hollow center and is therefore highly absorbent, accounting for linen’s legendary wearability in hot climates.

Linen manufacturers, concerned about the wrinkling “problem,” have developed ways of impregnating flax fibers with baked-on, wrinkle-resisting synthetic resins. But, observing that old, soft linens wrinkle less obviously than new, crisp ones, they’ve centered their more recent efforts on finishing processes that soften the linen. They’ve provided sand-washed, prewashed, stone-washed, steam-blasted, and tumbled linens, with the effect in each case being a gently rumpled fabric, quite different from the sharp, smooth, resinated linens.

Despite its wonderful response to dyes, linen has always been popular in its natural range of color, which accounts for some 50 percent of all linen production. Although often found in beautiful textured weaves (twills, herringbones, basket weaves), linens are usually not printed with designs. Embroidered patterns (see the photo above), however, are easy to find and hard to resist.

No fancy notions needed

Machine-sewing linen requires little in the way of special equipment. I use a standard needle in a size appropriate to the project, usually between 8 and 14. My stitch length is generally between 8 and 12 sts/in., again depending on the project. If I’m doing decorative topstitching, I choose a slightly larger stitch size. For edgestitching on a shirt, I follow tradition and use a slightly finer stitch. My favorite all-around thread is long-staple polyester, but I switch to silk or cotton topstitching thread for decorative stitching.

Linen requires nothing extravagant in the way of presser feet either, though you may want to invest in a felling foot if this is a treatment you plan to use often. If I’m edge- or topstitching, I can usually find something on my regular presser foot or on the machine bed to use as a suitable guide.

Match seams and finishes to the fabric’s weight

Since linen ravels easily and linen garments are often unlined, choosing the right hem and seam finish is important. The weight of the linen is the primary determining factor, along with the effect you’re after and how you plan to care for the garment. As always, the best way to sort through the many possible options is by testing.

French seams for lightweight linens

If your fabric ravels, don’t trim first seam of French seam until just before you sew second one.

Lightweight linens— Both French seams and flat-felled seams are wonderful for the lightest of linens, usually called tissue, handkerchief, or shirt weight, because the multiple layers of fabric these self-finished seams require won’t be too bulky in these fabrics. Linen is so easy to fold and manipulate that these seams are a joy to sew, even when slightly curved. And they’re sturdy enough for repeated washing, which is probably the way you’ll want to care for firmly woven, lighter weights of linen. The flat-felled seam is a better choice if you have sharper curves to negotiate or you prefer its decorative stitching lines. Rolled, topstitched hems are appropriate for these lightweight linens.

French seams for lightweight linens

If your fabric ravels, don’t trim the first seam of the French seam until just before you sew the second one.

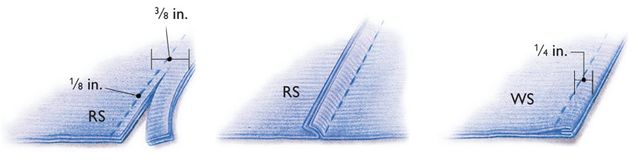

Steps 1&2 (left): 1. With fabrics WSs together, sew first seam 3/8 in. from raw edges. 2. Trim seam allowances to 1/8 in.

Steps 1&2 (left): 1. With fabrics WSs together, sew first seam 3/8 in. from raw edges. 2. Trim seam allowances to 1/8 in.

Step 3 (middle): Open layers and press seam allowances to one side.

Steps 4&5 (right): 4. Fold, then press fabrics, RSs together, carefully positioning first seam on folded edge. 5. Stitch the second seam 1/4 in. from fold, making sure no thread ends from trimmed edges get caught in seam.

Medium- to heavyweight linens— French and felled seams are probably too bulky for heavier-weight linens (experiment to check). Since many of these linens will be dry-cleaned and there may be a lining in the garment, less durable seams, including plain, welt, top-stitched, and slot, could all work well. If seam allowances are exposed (and if very loosely woven fabrics are lined), serged and zigzag finishes are sturdy and quick remedies for raveling. Seams can also be bound (but watch out for bulk), and a Hong Kong finish can be beautiful— one dressmaker I know uses bias-cut strips of Ambiance lining for this.

Rayon seam binding is also popular. But avoid polyester seam tape— it’s not bias, so it won’t behave the way you want it to; cut your own bias strips instead. Also consider simply turning under the raw edge and edge- stitching the fold, as I saw done beautifully on a recent Calvin Klein jacket. Treat hems as you would any moderately bulky fabric, covering the raw edge with seam tape or hem lace, and hand-stitching to secure the hem.

Hong Kong finish for unlined jackets

Cut 1 in.-wide binding strips from lining fabrics or silk organza. For curves, cut strips on a bias; otherwise, use straight-grain strips.

Steps 1&2 (left): 1. Sew strips, RSs together, to raw edge using 1/4 in. seam. 2. Trim seam allowances to 1/8 in.

Steps 1&2 (left): 1. Sew strips, RSs together, to raw edge using 1/4 in. seam. 2. Trim seam allowances to 1/8 in.

Step 3 (middle): Fold and press binding to WS.

Step 4 (right): Stitch in ditch of first seam through all layers.

Prelaunder linen

Shrinkage is an issue with linen, although some of the newer softening processes claim to have eliminated this problem. If you’ll be laundering the garment, it’s best to wash and dry it beforehand (if you plan to machine-dry the garment, do so at this point also). If the garment is likely to be dry-cleaned, steam-press it before construction. Be sure to dry-clean both pieces of a suit in order to keep the intensity of the color and the feel of the linen the same for the entire garment.

Press when damp— High heat is required to press linen properly, and steam helps, so it’s best to press it when damp. But it’ll scorch easily at such high temperatures, so be sure to use a pressing cloth. Linen also has a tendency to shine when pressed, so press it on the wrong side when possible. I like to use silk organza as a pressing cloth, as I can see through it, use high heat on it, and easily double it for more protection.

Linen, of course, starches well, and nothing looks sharper (while it lasts) than a perfectly pressed, brilliantly white, starched linen shirt. Pleats look beautiful in linen, and you may want to experiment with setting them the old way: Spray on a half-and-half mixture of white vinegar and water for crispness without the hardness of starch.

Underlinings, interfacings, and linings— best choices

Although their roles and functions sometimes overlap, underlinings primarily add support to the fashion fabric, while interfacings help shape a specific portion of the garment, and linings protect and cover seams, reduce wrinkles, and improve the hang of the garment. Whichever your garment requires, if any, your choices will be guided by experience as well as by experimenting with the fabrics at hand.

It’s best to start with the classic fabrics for underlining tests: cotton batiste, voile, silk organza, and organdy. All of these will add body without weight, and will give support to the fabric without dramatically changing its feel. Jackets, shifts, and dresses will benefit from the added substance that underlining provides, but it’s usually not needed in pants or blouses.

Good choices for sewn-in interfacings are muslin, silk organza, hair canvas, and self-fabric, depending on their availability and the degree of support your garment needs. Popular fusibles for linen are tricot and weft- insertion interfacing. But be sure that your choices of underlinings and interfacings can take the extreme heat needed to press linen (especially the fusibles). Also be sure to preshrink underlinings and interfacings, either by soaking them in warm water or by treating them with steam.

Because they’re intended to be comfortable in the hottest weather, many linen garments are unlined. When I do line linen, I use a cool, natural fiber such as China silk, spun silk, rayon, or cotton.

Look for patterns with shape, stitched details

A look through the pattern books for any season confirms the versatility of linen, which is often recommended as a fabric choice. Linen shows off every seam, curve, and detail, so it’s perfect for patterns with interesting seams, shaping, and surface details, such as pintucks, stand-up collars, welt pockets, gussets, contour waistbands, stitched hems, and the like. Linen would beautifully show- case the geometry inherent in the design of any pattern by Japanese designer Issey Miyake. The current patterns being put out by The Sewing Workshop similarly suggest linen, with their clean, geometric lines.

Yet this doesn’t mean that linen can’t be soft and flowing. My first choice for a linen project would probably be a loose, oversized shirt made out of handkerchief linen, à la Calvin Klein or Donna Karan. And in my wedding-gown business, I’ve made charming gowns from linen— no trains (not enough drape) but complete with bias-cut bodices, full, gathered skirts, bell sleeves, and touches of piping.

Linen-loving details

Linen provides the dressmaker with a wonderful base on which to create. Its unassuming nature lends itself well to highlighting design elements, and the ease with which they can be turned out in linen is an added pleasure. Here are a few details that work beautifully in this fabric:

Topstitching— Topstitching is almost a given on linen, and there are a few things you can do to keep it even and flat. When I plan to sew through a number of layers, I test first to check the appearance of the stitches. Each stitch should be clear and distinct, with no visible bobbin thread, so I may have to make some minor tension adjustments. And if I think shifting is going to be a problem, I’ll hand-baste the layers in place before topstitching.

If I’m combining topstitching with edgestitching, I make sure that both sets of stitching have been made in the same direction to reduce rippling. I don’t use backstitching, of course, which would thicken the line. Instead, I sew right to the end of the topstitched line, pull both threads to the underside, knot them and thread them on a needle, then bury them between the garment layers.

Linen pleats beautifully— Given its penchant for wrinkling, linen is obviously a fabric that loves to be folded and creased. To eliminate ripples, pleats must be folded precisely along the lengthwise or crosswise grainline. Some sewers pull a thread out along the foldline and use the open channel as a guide for grain-perfect pleats. However, to avoid possibly weakening the fabric, I rely instead on carefully following the grainline, which, in the case of linen, is clearly visible anyway.

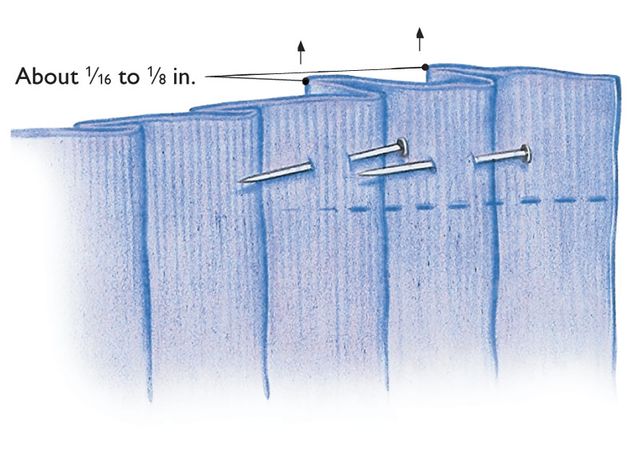

Once your pleats are pressed, you can reduce their tendency to splay open with a simple trick. As shown below (“Keep linen pleats from spreading”), pull the creased inside edge of each pleat a tiny bit toward the outside of the seam, pinning each one as you pull it, then baste on the seamline before you stitch the pleated section in place. It’s hard to tell you precisely how much to pull up each pleat, since this varies with different garments, weights of fabric, and pleat sizes, but as little as a 1/16-in. offset can make a noticeable difference to the fall of a pleated skirt or blouse. Carefully evaluate the results after basting, before completing the seam.

Keep linen pleats from spreading

To keep linen pleats from spreading, slightly pull up the inner creased edge of each pressed pleat; pin, then baste. Test fall of pleats before stitching the final seam.

To keep linen pleats from spreading, slightly pull up the inner creased edge of each pressed pleat; pin, then baste. Test fall of pleats before stitching the final seam.

Gathers— The lighter weights of linen love to be gathered. I always machine-sew three rows of gathering stitches, all in the seam allowance with the first almost on top of the seamline, taking the time to experiment to find the smallest stitch size I can pull. After you pull up the gathering threads (make sure they’re all pulled up equally), the more you play with the gathers to distribute them, the better they’ll look. Getting the tension just right is critical, too. If the tension’s too tight, you’ll probably break a thread as you play; too loose, and the gathers themselves won’t stay put.

I work gathers back and forth with my fingernails until they’re beautifully lined up, almost like tiny cartridge pleats. Once they’re where I want them, I press the seam allowance, flattening the gathers, which encourages them to stay in place for sewing.

Bound buttonholes— These look beautiful in linen, and are sturdy as long as they’re interfaced. The grain of the linen seems to complement their clean lines, and I can’t think of a more elegant or appropriate closure on a linen suit. But bound buttonholes wouldn’t make sense on anything lightweight. Apart from being out of place on a casual, oversized shirt, all the work behind the scenes would be too visible.

Piping— Piping works wonderfully on linen–it’s a clean, linear, well-behaved detail that’s totally in keeping with the fabric. But nothing looks worse than piping that’s rippling from being slightly off-bias, so I cut my bias strips as precisely as I can. (I use a triangle, careful measurements, and scissors— a rotary cutter works well, too.) I also hand-baste the sides of the piping strip together before machine-stitching them along the cording inside— pinning just isn’t enough to keep them from slipping. This tiny extra step virtually guarantees beautiful piping by eliminating even the smallest amount of shifting.

Linen shows off slot seams— I love the look of slot seams, which I’ve lately seen used on many linen garments. This seam is basically two pressed and abutted seamlines with extra-wide seam allowances that are topstitched to an underlay rather than sewn to each other. The actual seamline is in the center of the underlay, rather than where the topstitching is. The slot can be spread open wide, or not at all, and something other than the fashion fabric can be used for the underlay.

Slot seam allowances usually have to be widened (and adjusted if the slot seam is spread), because not only will they be topstitched away from the center, but there has to be enough fabric to finish off the seam allowances cleanly, usually in tandem with the edges of the underlay, by serging or machine-overcasting.

Godets— Using godets in the design of a garment is a wonderful way to add shape without the bulk of pleats or the fullness of gathers. On a skirt of heavyweight linen, for example, godets that start slightly above the knee would add walking ease and shaping along the hem, without adding thickness to the hip and waist areas. The extra weight that the godets add to the hem will also make the skirt less apt to show wrinkles.

To insert a godet into a seam, stitch the seam to the point of insertion, then attach the godet to one side, stitching from the hem to the insertion point. Stitch the remaining seam from the point to the hem, meeting the first seamline exactly at the point.

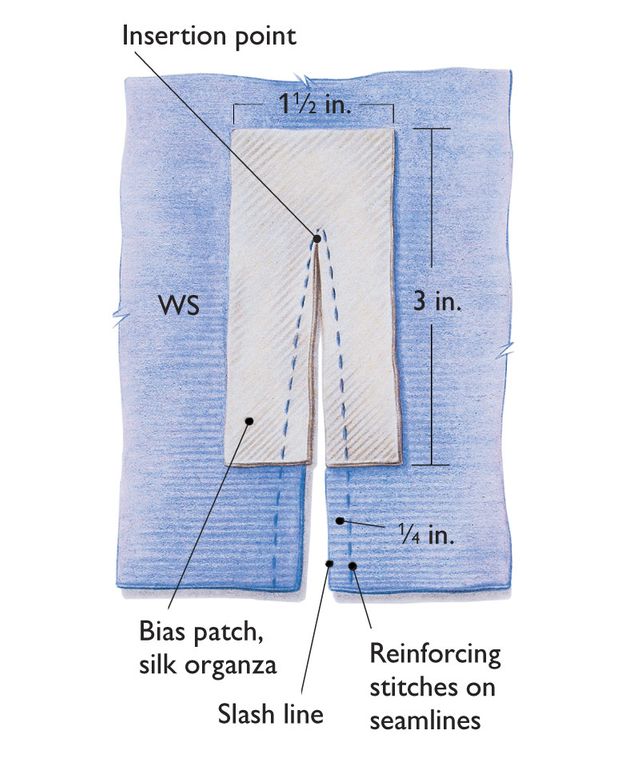

To insert a godet into a single piece of fabric, begin by reinforcing the insertion point with a rectangular patch of bias-cut silk organza, stitching it as shown in the drawing at right, then slash all the way to the point. Stitch the godet into the slash as described above, using 1/4-in. seam allowances (at least on the slashed fabric) and stitching exactly on top of the reinforcing stitches when you arrive at them.

Because the godet’s diagonal edges are usually cut partially on the bias, while the edges they’ll join are on the straight grain, you’ll need to be careful not to distort either side. If time permits, it sometimes helps to attach the godets for just a few inches on either side of the point, then let them hang for a day or two to stretch out before completing the seams. As with the other details described here, you’ll find godets done in linen easier to make than those made from almost any other fabric.

Reinforce slashed godet

To reinforce a slashed godet, back the insertion point with a bias patch of silk organza. After sewing reinforcing stitches, slash on the insertion line all the way to the insertion point. When stitching the godet in place, position it beneath the organza/garment layer so you can stitch exactly on top of the reinforcing stitches.

To reinforce a slashed godet, back the insertion point with a bias patch of silk organza. After sewing reinforcing stitches, slash on the insertion line all the way to the insertion point. When stitching the godet in place, position it beneath the organza/garment layer so you can stitch exactly on top of the reinforcing stitches.

Susan Khalje of Glenarm, MD, specializes in bridal couture. She is the author of Linen and Cotton and is national chairperson of the Professional Association of Custom Clothiers (www.paccprofessionals.org).

from Threads #65, pp. 32-37

Photo: Scott Phillips; drawings: Michael Gellatly

Thank you for this clear explanation of several elements of working with linen which I was foggy about.

Good article. Linen is such a nice fabric, I love natural fabrics so much!

Any ideas on how to keep it from scrathing. I love linen rayon blends, which at this moment is all I can afford, and I've made several pants and things with this linen blend but I have one pair of pants that cuts up my waist every time I wear them. There are thousands of tiny little needle like fibres sticking out of the fabric is there anyway of shaving them off or should I just line the inside of my pants at the waist?

at the top of this page it says: Linen comes in a wide range of colors, weaves, and intriguing blends. From top left, plain-weave linen; embroidered lace; crepe; gauze; burlap; embroidered plain weave; rayon/linen gauze; sateen; and various novelty weaves.

I have been searching for linen in a crepe weave (is this linen crepe?) for years since I was lucky enouh to get 3 m of it at Couturier Fabrics here in Ireland - it dyed beautifully and I very much want to get more. Can anyone help me?

My question is one I have had for a while but have not found a clear answer too! When making a lined garment what type of seam finishes are necessary--especially when sewing linen? If it makes a difference, the linen I am working with is dry clean only.

Thanks!

I have question for you experts. I have a lovely piece of metallic coated linen which is going to have to be dry cleaned after completion. How should I go about preparing it? I read that I should pre-shrink it by steam ironing it but my gut says not to do that since it has the metallic coating. Any suggestions ladies?

Thank you.

Amazing post,I am a linen lover.Always buy linen fabrics from Linen Club - it is a brand by Aditya Birla Group.The images are very nicely explained.

Linen is very lovely fabric, nice article.

VallyNicky, I'd bet money what you have is ramie, not linen. Unfortunately, there hasn't been much interest in labeling ramie accurately. Only flax is "real" linen, and it is very kind to the skin.

Well-written article. It opens up the possibilities of working with linen. It's certainly got my design-mind working overtime!

Linen has having properties which are canceled out if you combine it with other fabrics, so even threading of other fabrics may interrupt healing properties. Also, dry cleaning is unnecessary and toxic. If you plan to wear a lot of linen, invest in a washing machine with a wool care setting. This will work for linen. It's best to hang dry, but you can dry on delicate if you have to. Best part? No static cling.

For information on healing properties of linen : http://www.lifegivinglinen.com