by Karen Tornow

From Threads #109, pp. 70-73

For the innovative stitcher, it’s hard to imagine a more provocative material than felted-wool jersey. After a few machine-washings, the knit fibers in any wool jersey or double knit fuse, creating a completely nonraveling, almost leatherlike, yet still light, pliable, and inviting material. There’s no need for edge finishes, facings, linings, or seam allowances when sewing with this easily produced fabric, which makes it perfect for a host of quick and inventive construction and appliqué techniques.

Felt first or embellish before felting

At first, I felted all my wool jersey yardage as soon as I got it home, thinking only of the interesting things I could do with an already-felted fabric. But it wasn’t long before I discovered the often more interesting results you can get by manipulating the unfelted fabric in some way before washing it — stitching on it, wrapping it, slashing it, layering it, and so on. To put these discoveries into context, I’ll take you on a tour of four felted-wool garments, describing how I proceeded in each case and suggesting alternatives. But let’s begin with the felting itself, and how to factor it into your sewing plans.

Wool-felting basics

As the felting process does its magic, it shrinks the fabric lengthwise by at least a third, and somewhat less crosswise. Typically, wool jersey yardage is 56 inches wide, but for a felted project I use the yardage recommendations for 45-inch-wide fabric, and buy twice the needed amount, which allows plenty for the project and the samplemaking and experimentation that are involved. Any all-wool jersey or double knit will felt, but the results will vary, depending on the qualities of your fabric, and how many times you wash it. Solid colors are my usual choice, but patterned fabrics can be interesting too.

The felting progression: Three washings are usually needed to get dense felted textures.

To felt yardage, first fold it in half and machine-baste the selvages and cut ends together about 1/4 inch from the edges. This helps reduce edge curling and grain skewing. Fill your washing machine with your hottest water and add detergent before putting in the fabric (don’t pour it on the fabric), then select the longest cycle available. Don’t crowd the machine, or mix very different colors, since dyes can run. If you’ve cut multiple lengths or pieces, wash them together so they’ll have the same texture.

Three wash cycles are usually enough for me to get felting I like, but it’s good to measure your yardage between washings to be sure it isn’t shrinking so short you no longer have enough for your project. To get more shrinkage, you may be able to reset and repeat the agitation cycle on your machine. You can add boiling water to raise the temperature (hotter water increases the felting). Skip the detergent after the first wash and bypass the rinse cycle as it usually uses cold water. After each washing put your fabric through a normal hot cycle in the dryer. When you like the looks of your fabric, the felting is done.

Steam, don’t press

Remove or cut off the basting. Then, using a wet press cloth, steam the fabric before cutting; don’t touch the felted surface directly with the iron, and be sure to let the fabric cool and dry before you reposition it on the ironing board. During and after construction, keep the iron’s soleplate away from the right side of the fabric, so you don’t flatten the texture or create shiny marks.

Try it out! Make a pillow to try felted jersey on a small scale. Layer contrasting colors, stitch a pattern of random squares, then cut away the top layer. Leave all edges of the cut “fringe” unfinished.

Plan before cutting

Try it out! Make a pillow to try felted jersey on a small scale. Layer contrasting colors, stitch a pattern of random squares, then cut away the top layer. Leave all edges of the cut “fringe” unfinished. ![]() Before you cut into your felted yardage, it’s important to have a plan for your construction methods (lapped or conventional seams; facings; hems) and your embellishments if decorative hem edges are involved. I always figure out where I will (or won’t) need seam and hem allowances, and mark them on each edge of the pattern before cutting, so I don’t have to trim anything later.

Before you cut into your felted yardage, it’s important to have a plan for your construction methods (lapped or conventional seams; facings; hems) and your embellishments if decorative hem edges are involved. I always figure out where I will (or won’t) need seam and hem allowances, and mark them on each edge of the pattern before cutting, so I don’t have to trim anything later.

I use a rotary cutter when cutting all but the most complex shapes, using rulers and other cutting guides for precision, especially when using lapped or butted seams (see Threads No. 103, pp. 58-61 for more on lapped seams), and whenever the cut edge will be exposed. To cut into corners, I use a buttonhole cutter, which looks and cuts like a small chisel, but small sharp, pointed scissors work just as well. If notches are necessary, I cut them extending from the edge, and clip them off when no longer needed.

When manipulating the fabric before felting, I measure each piece that will be enhanced, then apply whatever treatment I’ve chosen to twice the width and length of fabric required.

Four felted jackets, and more embelishment ideas

Check out the links below for more detailed descriptions of my construction and embellishment strategies, as well as photos of finished garments. If you discover any other neat ways to take advantage of felted wool’s wonderful qualities, please post your ideas (and photos) on Gatherings, the discussion forum of Threads magazine.

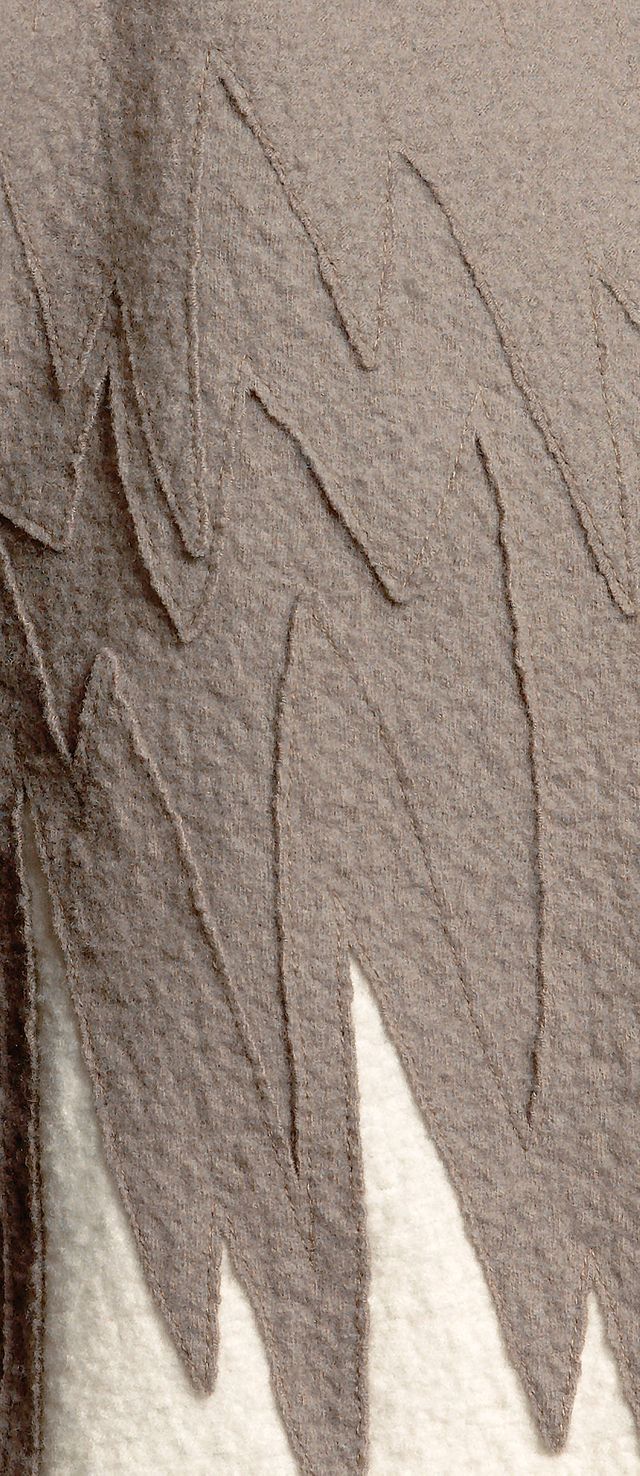

First felt, then overlap and cut icicle shapes.

Karen Tornow made a tissue tracing of each major pattern piece (Kwik Sew 2809), and drew on them the icicle-shaped lines that would divide the garment into two colored areas. She cut out the entire garment in the felted darker fabric, joined all vertical body seams, then layered these over a wide strip of the felted lighter fabric, and stitched the icicle shapes using the marked pattern tissues as tear-away guides.

|

|

She trimmed away the excess fabric on both sides, then used the cutoff portions for subsequent appliqué layers. The sleeves were constructed similarly. All the seams were lapped and double-stitched and all the edges were left unfinished.

Photos: Jack Deutsch; makeup: Susana Perks

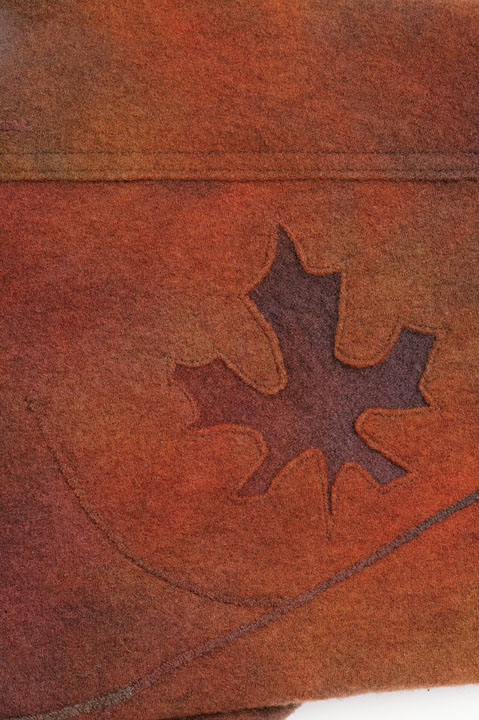

Felt first, then create reverse appliqués.

The author cut out this jacket without knowing where she’d place the reverse appliqué leaves. The sleeves had to be pieced because the felted fabric wasn’t wide enough to cut them as intended by the pattern (The Sewing Workshop’s Inventor Shirt, modified). All the seams were lapped and double-stitched, and all the edges were left unfinished.

To simplify the appliqué, she sewed as many seams as possible to still allow the garment to lie flat.

|

|

Tracing real maple leaves to create her appliqué patterns, she arranged felted leaf cutouts (disregarding grain direction) on the garment until she found a pleasing design. Each was pinned to the wrong side and edgestitched in place, then the top fabric was cut away to reveal the inset.

The vine design was added by couching 1/4-inch felted strips with a wide zigzag stitch. The buttonholes are rectangular stitched boxes backed with a felted scrap and slashed within the stitching.

Model photo: Jack Deutsch; details: Scott Phillips; makeup: Susana Perks

Other effects with felted fabric

Among many other options, felted fabric can be used with raw edges cut in decorative ways (left); pieced, using butted seams (center); and couched and beaded (right).

|

|

|

![]()

![]() Photos: Scott Phillips

Photos: Scott Phillips

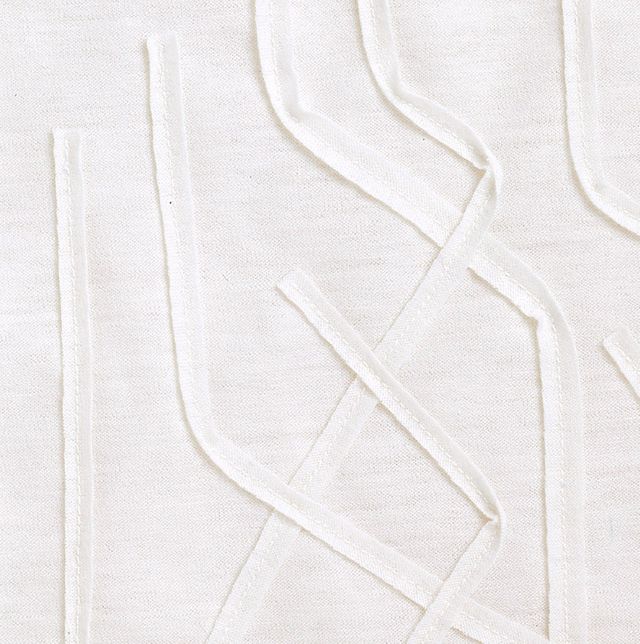

Apply sinuous strips, then felt.

From unfelted fabric, the author cut pieces equal to twice the needed length for both the front and back of the jacket at left (Vogue 2279), setting aside material for the plain felted sleeves. She next cut many 1/4-inch-wide lengthwise strips and arranged them on the pieces that were to become the front and back. She started with a few long strips, pinning them in improvised patterns of sparsely intertwined angled lines and working away from one narrow edge on each body piece (see detail photo).

![]() In order to sew lapping strips, she marked the path of the top strip on the background with pins and removed it, sewed on the strip beneath, then followed the pins to sew on the top strip. She filled in her design in the same manner using progressively shorter strips. After felting all the pieces at once, she constructed the garment with lapped and double-stitched seams. All edges were folded to the wrong side and secured with hand stitches.

In order to sew lapping strips, she marked the path of the top strip on the background with pins and removed it, sewed on the strip beneath, then followed the pins to sew on the top strip. She filled in her design in the same manner using progressively shorter strips. After felting all the pieces at once, she constructed the garment with lapped and double-stitched seams. All edges were folded to the wrong side and secured with hand stitches.

![]()

Model photo: Jack Deutsch; detail: Scott Phillips; makeup: Susana Perks

The selvages of this fabric formed tight curls when felted, which she cut off to form tie closures. The collar is a double layer, the inner one of which was cut with the long edge on the selvage, and this selvage rolled over the raw edge of the other collar layer and was hand- stitched in place.

Apply small scraps, then felt.

The author first measured the combined length of the front and back body pieces (Vogue 2615) that she planned to enhance, then cut twice that amount from unfelted fabric. Material for the plain felted sleeves was set aside.

Model photos: Jack Deutsch (above) and Scott Phillips (right); details: Scott Phillips; makeup: Susana Perks

Next, she cut many 1/2- to 1-inch fabric squares, and using a variegated cotton thread, she stitched lines in a random pattern all over the body piece, occasionally tucking a square under the needle. After felting both treated and untreated pieces, she trimmed the felted squares close to the stitching. All the seams were lapped and double-stitched, and all the edges were left unfinished.

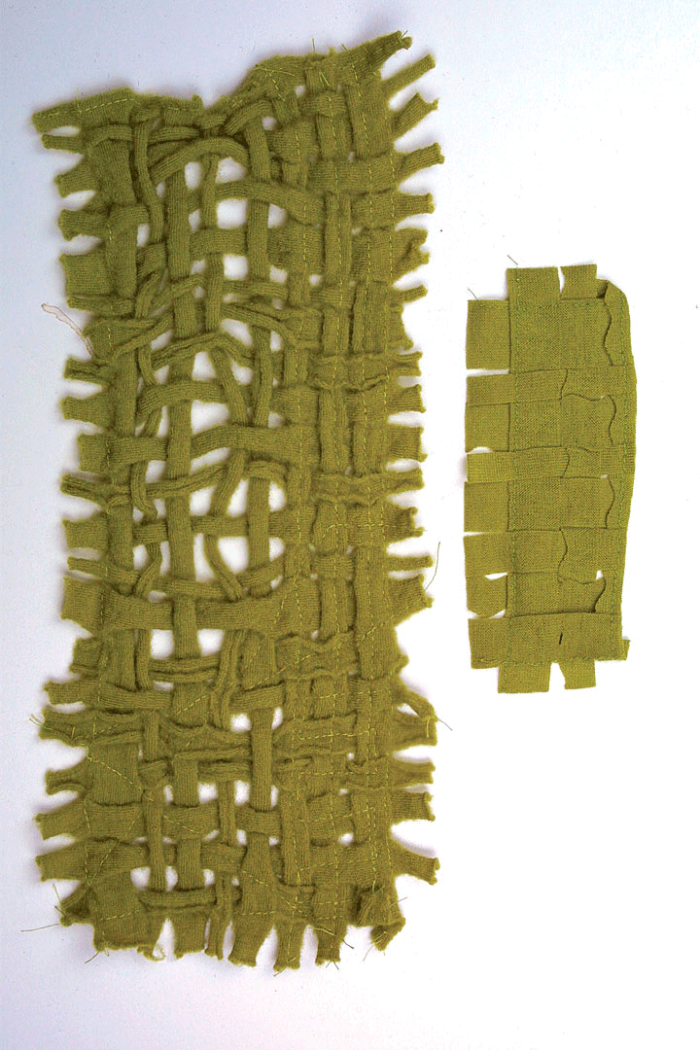

Other effects to create before felting.

Unfelted jersey can be cut into strips and woven. Stitch around the edges of the weaving before felting to secure them. By wrapping rubber bands tightly around selected sections, shibori-like textural effects can be achieved. The band can even be cut off after felting, creating ravel-free holes. Appliqués added before felting, and placed without regard for grain alignment, created interesting textural as well as color contrasts. Experiment to find other options.

|

|

|

![]()

Photos: Scott Phillips

Karen Tornow writes and designs in Corvallis, Oregon.

So glad to see a fellow Oregonian on this site. I'm a newbie at felting but am enthralled with the technique. Recently I acquired 4 yds of some sort of wool at a yard sale (for $5.00!) and I want to make a jacket out of it after pre-felting. I sampled it out, washed and dried to pre-felting specifications but I notice that it did not shrink very much, although the edges are stable and the texture did change. Now I am wondering if this is a wool blend. If so, can I still felt a design into it?

Annie

I am looking for an issue of Threads that had an article about making wool pants -they were gardening or work pants and I think the article was before 2001. Anyone Know?