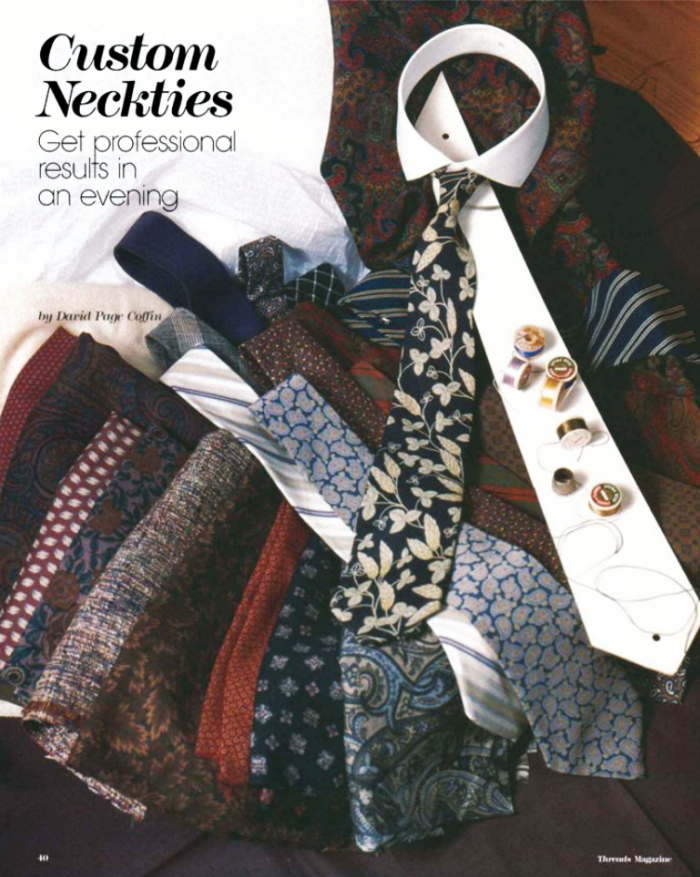

I still happily wear the very first necktie I ever made. If you use the construction methods that I’ve learned since, I think you’ll also find that making neckties is easy. A beginner could certainly make the first one, including the pattern, in an evening. After that, a tie in two or three hours is a snap.

Tools and materials

• Outer fabric, lining, and interfacing.

• 45-degree triangle, yardstick, 18-inch-square scrap of stiff cardboard, pencil, and craft knife.

• Needle, silk buttonhole twist, and silk pins

• Sewing machine, for one tiny seam and for lining the tip (all else is hand-sewn)

• Rotary cutter or scissors, the cutter is ideal because you’re dealing with all straight lines

• Iron and ironing board, which is just the place for the hand sewing; it’s the perfect length.

Choosing fabric and interfacing

Almost any thin, firmly woven fabric that looks good on the bias (see illustration at left, below) will make an attractive tie. The only limits are that it can’t be so thin or so loosely woven that it’s transparent, nor so thick that it will make an awkward knot; nor should it wrinkle easily. Ideal fabrics include most lightweight and medium-weight silks, wool challis, Viyella (a wool-cotton blend), all-cotton Liberty prints, and even quilting cottons. Whatever you choose, get 1/2 yard, which is plenty for two ties if it’s at least 36 inches wide. Most stores add about a 1-inch cutting allowance, so you’ll have 19 inches of fabric. For extralong ties, get 3/4 yard. Because the tie is cut on the bias, the fabric stretches as you work with it. Cotton stretches less than silk, so it’s a good choice for your first tie.

Real necktie interfacing is hard to find. B. Black and Sons (BBlackandSons.com) carries wool tie interfacing. TheThackery.com offers a number of options, including precut interfacing and a sample assortment, so you can see which you like. Try to find the 45-inch-wide variety. Buy at least 5/8 yard.

A blade form for layout

The best way for you to make a tie that the owner will wear is to copy the shape and thickness of his favorite one. In the process, you’ll make an essential tool: a blade form. The blade is the front of the tie, from the point to the start of the narrow part that will eventually encircle the neck. This cardboard form serves as the pattern for your tie and interfacing. You’ll also use it to fold and press each tie you make. The tie also has a narrow harrow, which is behind the wider point when the tie is worn. Both ends have a “tip” or “point.” You’ll see all these terms used in the steps that follow. On some ties, the narrow half tapers from its point to the neck area. I prefer the narrow half’s sides to be parallel from the neckline portion to the tip.

1. Draw the exact 45-degree diagonal on the cardboard square (mat board from an art supply store is perfect). Center the model tie along it with the point matched to the corner. Check the corners and the diagonal with your right triangle, also sold by art supply stores.

2. With a pencil, outline the tie blade shape. Then remove the tie and, with your yardstick as a guide, straighten the pencil lines, making sure they’re centered around the diagonal. Cut out the tie shape accurately, using a craft knife.

3. Square up your fabric, and chalk a 45-degree diagonal from the bottom-right corner. Center the blade form on the diagonal with the point positioned 3/4 inch inside the corner (for the seam allowance) and chalk the outline drawing (at right, above).

4. Carefully flip the form over to one side of the outline, then to the other, to draw the outer edges of the piece. Don’t worry that the point of the form hangs off the end. The fabric will be cut three times the width of the form.

5. Measure and outline the tie’s narrow half. I prefer the narrow half of the my tie untapered; it’s a little easier to make, and it’s much easier to untie, so the tie lasts longer. To cut this part, measure the fabric width that you’ve established where the blade runs off the top of the fabric (usually about 3 inches—see length A in the drawing above).

6. Mark off this length along the fabric’s bottom edge. Then, with the right triangle and yardstick, draw up from the marks two parallel, 45-degree diagonal lines running to the top of the fabric.

7. Draw in the point. Use the triangle as a guide for accuracy.

This will make a finished tie that’s 52 inches to 56 inches long, depending on the fabric’s bias stretch and the fabric salesclerk’s generosity. There’s 2 inches for seam allowances, 3/4 inch at each point for the lining, and 1/4 inch (times two) for the middle seam. For a longer or shorter tie, figure about a 3-inch total change in tie length for each inch more or less than 19 inch of fabric length. Cut out the tie, and with right sides together, machine-stitch the short seam to join the blade half to the narrow half.

Making the interfacing and lining

Cut the interfacing on the bias, just like the tie fabric, using the blade form as the pattern. Depending on how thick a tie you want, you can use one or two layers of interfacing. Most commercial ties don’t have interfacing in the blade tip, but it’s a classy touch, and it’s necessary on lightweight fabrics. If you interface to the tip, put the point of the blade form at the corner of the interfacing (no seam allowances) and cut out along each side. If you don’t want to interface the tip, position the form on the interfacing so the point is 2 inches or 3 inches from the corner, then cut the tip off after you’ve cut it out.

For the narrow half of the tie, use the triangle and yardstick to mark and cut a bias interfacing strip the width of the finished tie at that end. You don’t have to interface the tip at the narrow end; the interfacing should end about 3 inches from this tip. Join the interfacing pieces by slightly overlapping the ends and zigzagging over them.

Now you’re ready to line the point by machine (see “Lining the tip” illustrations below). The idea is to start stitching the seam at one edge, right sides together, and fold out the excess material at each corner, just as you get to it; this seam is sewn in two parts, with the excess length pleated out horizontally (see Steps 2 and 3 illustrations below). The lining, cut smaller than the tip, will fit nicely inside when all is turned and pressed flat. You can use scraps of the outer cloth for the lining, which is another classy touch, or any contrasting lightweight material.

The form and finishing

Once you’ve lined both points, lay the tie face down on your ironing board and position the blade form on top with its point matched to the tie point. Traditionally, ties are closed so the left side overlaps the right when seen from the back. Fold the underlapping side over the form and press it without creasing or stretching the fabric. Fold the overlapping piece in half by matching its raw edge to the outside edge of the form, press the fold (see the photo below), and press the whole side over the form to the middle of the tie. The fold should be right down the center of the back of the tie.

Shape the narrow end by eye—you don’t need a form. Then open up the tie and lay in the interfacing. If you’ve included the tip at the wide end, arrange it so that it’s about 1/8 inch shorter than the lined tip, but don’t put the interfacing inside the lining yet. Slip the form under the interfacing, but slide it toward the tip a bit so it’s narrower than the interfacing. Pin the fold closed, with the pins parallel to it. The outer fabric should be snug, but not stretched across the interfacing (see the photo below). Your closing stitches will go through all layers except the front of the tie.

Thread a needle with silk buttonhole twist, but don’t cut the thread; work with it still winding off the spool. You’ll cut it when the tie is closed, leaving about 2 inches loose at each end so the tie can stretch. Start the slipstitch that closes the tie just above the tip lining (see the “Finishing” illustration above), and end it about 3 inches from the narrow tip.

When you’re done, remove the form, open the tie gently, and tuck the interfacing inside the lining. Finish the closing with a bar tack at each end, about 1 inch below the ends of the slipstitches, sewing through tie back, lining, and interfacing.

For a final touch, make a loop with the tie fabric that’s wide enough so that when it’s sewn to the back about 6 inches from the tip, the narrow end will fit inside and won’t sway out when the tie is worn. You can be sure it will be worn proudly, especially if the owner picks out the fabric.

Can anyone explain how to follow this instruction, “but don’t cut the thread; work with it still winding off the spool. You’ll cut it when the tie is closed, leaving about 2 inches loose at each end so the tie can stretch.” I can’t figure out how to hand sew without cutting the thread.

The slipstitching to hold the tie together should be one piece of thread – you don’t want to cut the thread too short and have to knot it, because that would prevent the full tie from stretching. To make sure you have enough thread, don’t cut it from the spool, and don’t knot the thread at the start. Make the stitches, keeping them long and relatively loose as they alternate from side to side on the back of the tie.

Pull through more thread from the spool if you need it as you go. The buttonhole twist is strong and slippery and should slide easily without breaking.

Once the tie length is slipstitched, stretch the tie, then snip the thread at each end as instructed. You can hide the 2-inch thread ends on each end of the tie by burying them in the fabric, but don’t knot them. You’ll make separate backtacks at each end to secure the seam. The thread for the slipstitches is meant to “float” unsecured so the tie can tie and drape properly.

Cheers, Sarah and Carol - Threads editors