Natalie Chanin’s Journey Home: Reflections From the Slow-Fashion Innovator

A conversation with the groundbreaking thinker and champion of makers

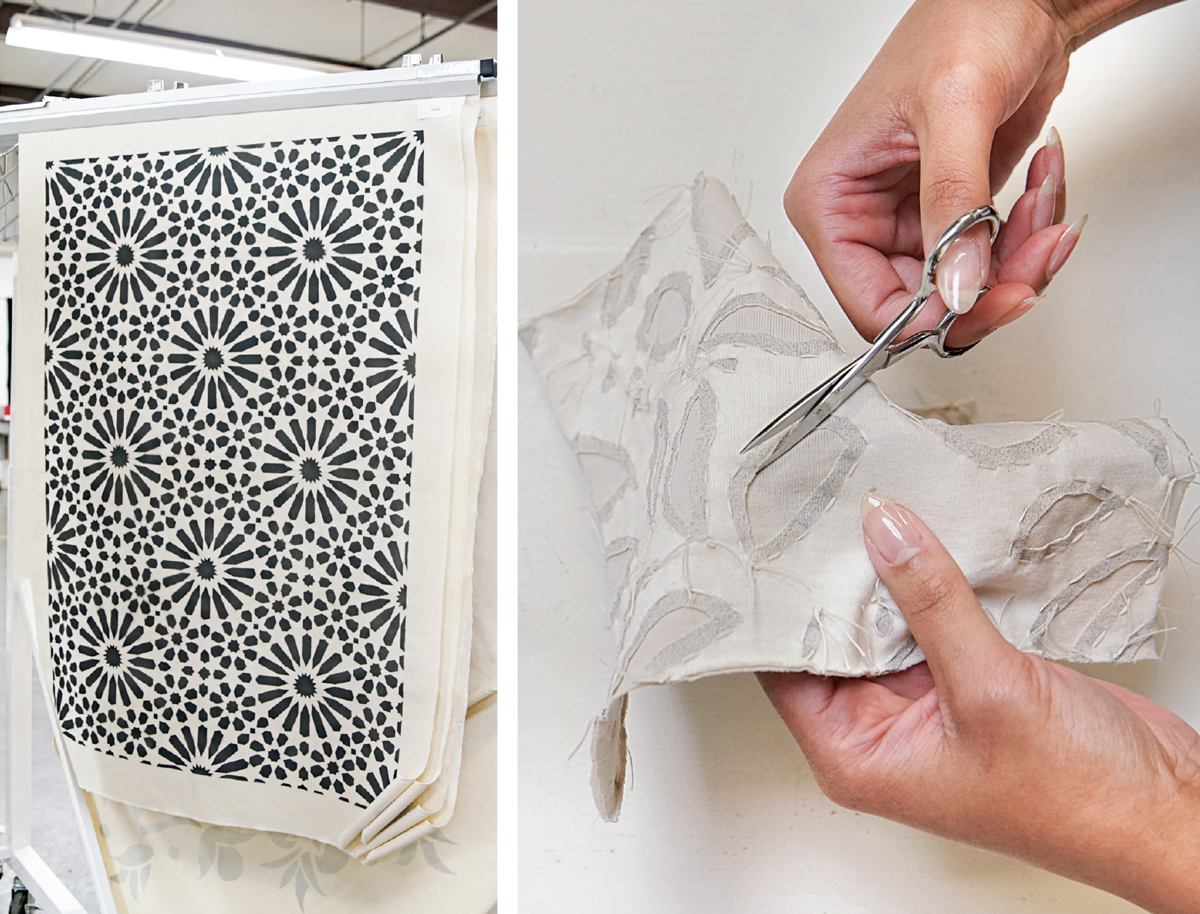

The founder and designer behind Alabama Chanin is one of the most creative artists and entrepreneurs working today in sustainable fashion and textiles, sewing, and embroidery. The company’s Florence, Alabama, headquarters is the heart of a thriving ecosystem of artistry and industry where you’ll find collections of one-of-a-kind, hand-stitched designer garments as well as sewing patterns, fabrics, kits, and workshops sold through the company’s education arm, The School of Making. The Alabama Chanin community also extends to its Project Threadways not-for-profit offshoot, collaborations with artists, and a wide community of makers stitching and embellishing in the Alabama Chanin way.

To celebrate Natalie’s newest book, Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and The School of Making (Abrams, 2022), looking back on 21 years of the company she founded in her hometown of Florence, we had a wide-ranging conversation. We talked about sewing, sustainability, and her compelling story of leaving a career as a fashion stylist in New York and Europe and returning to the Muscle Shoals region. There, she sought out women who knew hand-stitching techniques from the quilting tradition, and began designing and sewing timeless garments, often richly embellished. In the process, she built a technique library that she then began to teach and share. I found her story to be one of grace, intuition, adventure, and a love of artisan craft, all rooted in a time and place where Natalie’svision emerged and grew.

Editor’s note: Our conversation has been edited and excerpted for length.

Writing the story

Elaine Lipson: Let’s start with the new book. After writing and publishing five books for makers, what inspired you to write Embroidery now?

Natalie Chanin: Well, there definitely has been this thing at the back of my mind of telling the story of how all this came to be, as I’m getting older and thinking about a succession plan, and wanting to get some things down on paper. I explained to [my editor] what I thought it was, trying to tie all these things together to tell the whole story of the company and my path home to the company, and that’s where it went. As an organization, we don’t really fit into traditional craft. We don’t really fit in the fashion industry. We don’t really fit in the design industry. We fit somewhat in the craft industry, but it’s also not just a craft company.

And you know, I always wanted to do a book that had these big, beautiful pictures of fabric. All these different things came together, all these different parts of the company coalescing in one place, and the story of our community. My career has been deeply impressed by the community of makers here and the industry that grew up in this region, the cotton. And then, coming home and hearing all these stories, and beginning to collect oral histories, this work made a deep impression on what I wanted this company to be and added to our story of making. I wanted to show the importance of making in the past, the present, and on into the future.

EL: When you came back to Alabama, did you know that you would stay?

NC: No, no, I thought I was here for just a month or two, and then I thought I’d be here for three or four months after that, and then it was six months, and then it was a year. I think in 2006 when [daughter] Maggie was born, I began to understand that I was home for good. But even then there were moments where I thought maybe we would move somewhere else. I never thought it would be a 20-year adventure, 22 years now.

EL: I was struck by all the ideas you brought together: These experiences that pulled you toward home, and also environmental design, physics, open-source technology, collaboration, music, woven together with stories of essential techniques like the straight stitch. Have you always had this desire to connect fashion and textiles to so many other things in the world?

NC: I definitely think I’m able to connect seemingly disparate ideas together into some sort of overarching story. That is how my mind is built, and I do really enjoy working that way. I love multidisciplinary studies, and part of that is probably why I was so drawn to a Bauhaus education, where all of these different people from different disciplines work together. [Natalie studied at North Carolina State University.]

I can’t stress enough how Bauhaus-type training created a path for me that felt like I had landed where I was supposed to be. I’m very curious, and I love this idea of planting a garden and seeing what grows. My uncle used to say I rose when the birds start singing in the morning—I still can’t sleep past the first birdsong. I wake up and think, today’s the day!

The School of Making and Hand Sewing

EL: In the book, you talk about garment as narrative. Making an Alabama Chanin garment takes time; you live a story through the time that it takes to do hand stitching. Do you worry that people are not patient enough to find that anymore in sewing?

NC: I feel like it’s just the opposite. I feel like we are craving something that we can dig into and crack open. I think that’s what you see through our workshops. More people come for workshops than ever before, despite the troubles with travel now. And I think there’s a great opportunity for us to connect over this kind of craft going forward, in all kinds of crafts, not just sewing but cooking, woodworking, and all kinds of making. As humans, we are hungry for that connection of hands, heads, hearts, and minds.

EL: The School of Making is the educational and the do-it-yourself arm of Alabama Chanin. Why has it been important for you?

NC: It started with wanting to preserve techniques, because when I first came home and we began this work, the age range of our sewers was older and there wasn’t a younger generation rising behind them.

I envisioned open source originally in just a fit of thinking, “If everybody—including larger companies—is copying [the Alabama Chanin style], we might as well share the techniques we created, and show people how to do it.”

I wasn’t sure where that was going to go, but then the books came out and it became a strong and important part of our business model.

One thing led to another, and we just kept doing the books and started making the kits. Our team continued to work the path, and that’s what we did.

Everybody asks, “What’s the secret sauce?” So you look back, and it’s very unsexy to answer that it’s just getting up every day and having this list, and you work your list and do the best you can that day, and try to make the right decisions. And then the next day, and then 20 years later, 365 days times 20 years.

EL: What’s the most popular kit from The School of Making?

NC: It does tend to change over time, but the swing skirt and the corset, which were from the first book [Alabama Stitch Book (STC Craft, 2008)], continue to be some of the most popular kits.

We just started doing some different kinds of workshops; we did an outerwear workshop that was only about coats. We’re probably going to have some workshops that are more about creativity and process and color exploration, fabric design, things like that.

I’m hoping that those become the popular ones. It’s fun to get a kit that we’ve designed and to do that, but I think it’s also really fun to design for yourself and create, take it to the next level, design your own stencil, plan the whole thing out. I think that’s the next progressive step based on this book.

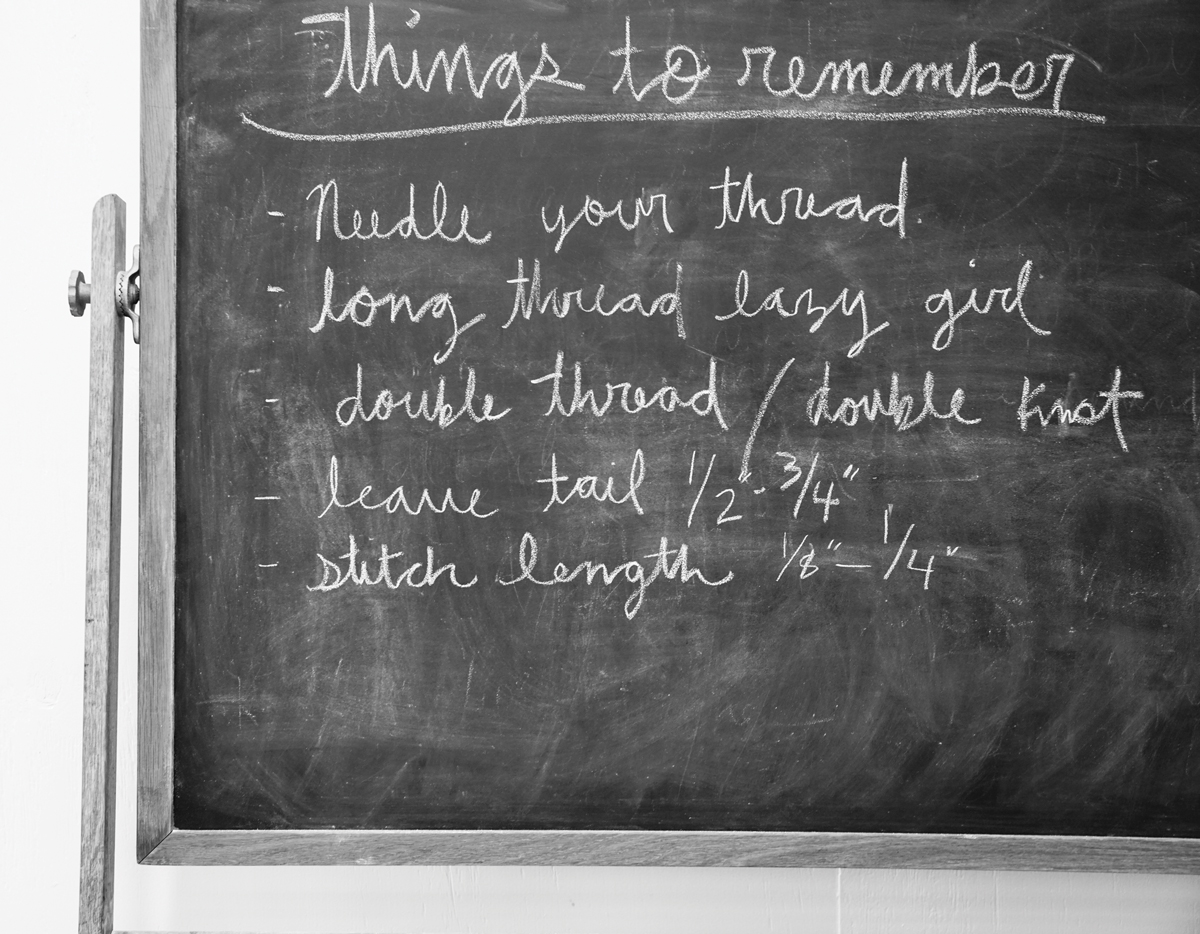

EL: For garment sewers who sew by machine, what’s a good place to start with Alabama Chanin hand-stitching techniques?

NC: All of those skills that they’ve learned in construction—those are not going to be lost. If you understand construction, you’re going to be able to do some of our more advanced patterns. If you’re really interested in embellishment, and have not done much embellishment by hand, starting with some of our smaller projects—we have a little journal kit, and we have a Swatch of the Month—is a great way to learn techniques.

But for anyone who has learned sewing, it’s not totally different. It’s just by hand instead, and there are a few little rules that you have to learn. We have different seam allowances, we leave our edges raw. There’s some things we do that people would probably say, “That’s not really how you do it.” But we do it that way. I’ve always said, let the materials talk to you, they’ll tell you.

I make the joke that nobody’s going to come up to you in the grocery line and be like, “Excuse me, ma’am, but you know that dart is felled the wrong way, right?” And if they do walk up to you and say that, you know they’re probably going to become one of your friends or join your circle of trusted people.

How we run the business and how we teach the workshops are two different things. We’re selling [finished] clothing that is very expensive, and people are buying it as an heirloom piece, and they expect it to be perfect, so we really do strive for the highest possible quality.

If I’m sewing, I want to have the enjoyment of it. If I make a mistake, I don’t want to go back and take it out. I’m going to sit and enjoy, work the puzzle, listen to a book on tape while I’m doing it. I want to settle into the process. I think that’s why I love hand sewing.

Hand sewing is just so simple. There’s this thread, there’s a needle, there’s a pair of scissors and two pieces of fabric, and it makes me feel very calm and happy to do that work. I don’t like to be hurried. I don’t want it to be perfect.

EL: Your techniques lend themselves naturally to stitching in groups. Does this community aspect come from the quilting legacy of your grandmother and other people?

NC: I did think about the quilting stitch when I first came home, and about these quilting bees. But it was more that I was looking for people who could do this work. I wasn’t thinking about how the workshops were going to create this giant community. That wasn’t really in my plan. But . . . people love to sit and commune together, the same way that my grandmother loved to commune and sit with her friends.

Quilting happened at the end of the summer, after all the food had been put up for the year, when it started to get cold. Women could finally sit down and visit with their friends. It was a time of communion with their community. And those two words are so beautifully connected. So I think, what could be better? Food, fabric, a group of good friends together, add a glass of wine, and what more could we want from life? I didn’t really see how big this community was going to grow. It seems like the people who needed to find it found it, and they’re with us, and it’s grown very slowly and organically over a 20-year period.

Continuing the journey

EL: In your book you say, “One part is forever inspiring the next.” What’s next for you?

NC: I am working on a succession plan and what Alabama Chanin looks like when I retire and go on. I don’t see myself fully retiring. I’d like to teach in a different way, I’d like to continue to write books, I’ve done some artist residencies. I think I’ll continue to work and do things until I fall over, because it’s just my nature—and my nurture. I’m really hopeful right now for a bit more time and space to be able to dream a bit more and have less responsibility in the day-to-day running of the business. That’s where I am today.

Should life give me the opportunity to have another story, then I’m hoping for space and time to be able to explore and do the same kind of work I’m doing now but with more intention, more time for it to unfold, more thoughtfulness, more walks, more photography, more words.

EL: We need to pass these ideas of home, community, and making on to the next generation, right?

NC: Yes, and I have been home for a long time, and of course COVID made that very clear, so I’m looking forward to getting back out in the world.

You know, the thing about home: Every place that I’ve lived, I planted a garden and left it. Every place that I was, I made it my home to the best of my ability. I needed that for myself. I took my own home with me and dug in the dirt and planted gardens and made friendships and cooked dinners and organized events just like I do now. It’s not really any different, I was just kind of carrying my home with me.

When I came back here, I settled into my home. And more than anything I embraced it, because as a child I was trying to run away from it. The horrors of the ’60s in Alabama—there’s nothing I can do to change what happened here, and there was a lot of shame around it. The people who were hurt, the people who lost opportunities . . .

But I can try to make a better story today with the skills and the gifts I have. So I took all those stories with me out into the world and it’s been a constant gardening of those stories, you know, unearthing, planting, growing, changing, eating, planting, growing, as the seasons unfold, trying to unpack it all and what that meant.

We carry home with us no matter where we go.

Sew Your OwnThrough Alabama Chanin’s open-source learning model, there are many resources to help you learn to make your own Alabama Chanin-style garments and join their community of stitchers. Books Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and The School of Making (Abrams, 2022) The Geometry of Hand-Sewing: A Romance in Stitches and Embroidery (Abrams, 2017) Alabama Studio Sewing Patterns (STC Craft, 2015) Alabama Studio Sewing + Design (STC Craft, 2012) Alabama Studio Style (STC Craft, 2010) (out of print, buy used or check your local library) Alabama Stitch Book (STC Craft, 2008) The School of Making • Explore patterns, fabrics, kits, stencils, notions, workshops, and more at The School of Making at AlabamaChanin.com. • Join The School of Making Stitchalong group on Facebook. Video of learning Craftsy.com offers three video classes with Natalie Chanin and The School of Making. In-Person Workshops • Alabama Chanin workshop schedule: AlabamaChanin.com in The School of Making section. • Ask around locally to find an Alabama Chanin stitching group— or start one. Inspiration Follow the Alabama Chanin Journal and follow @alabamachanin and @theschoolofmaking on Instagram. |

Elaine Lipson (ElaineLipson.com) is a writer, editor, author, and artist.

Elaine Lipson (ElaineLipson.com) is a writer, editor, author, and artist.

View the PDF version by clicking below:

View PDF

Thank you! Natalie has been an catalyst and guide to so many! Her vision and gifts are amazing!

Thank you for your lovely comment. Yes, she has! — Elaine Lipson

I have made 12 different Alabama Chanin style garments. I have five of her books. I have used their stencils and techniques. Each piece took several months and was very satisfying to make. Each piece is unique and I am very proud of myself for putting in the effort. Thank you Ms. Chanin for your inspiration.