Designer Creates a Menswear Collection with a Twist

A designer draws from history's best-known hoarders to create four ensembles

While completing his fashion design studies this past year, Christopher Lagasse couldn’t get enough of a headline-grabbing story from the 1940s about the so-called hermit hoarders of Harlem. In fact, Lagasse based his final garment collection on the eccentric brothers, Homer and Langley Collyer.

The Collyer brothers had come from high-class society but gradually descended into a life of chaos, secluded in their debris-packed, four-story brownstone. Both died in 1947 amid their tons of collected junk.

“It’s one of the most fascinating stories I have personally ever heard,” Lagasse says. “I became kind of obsessed with it.”

A touch of chaos

With the brothers in mind, he created his four-look collection, “From Riches to Rags to Riches.” It was his senior project at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Each carefully constructed garment was given some kind of “chaotic twist,” he says. The elegant smoking robe, for example, turned into an open hospital gown in the back, to represent being in a sanitorium. “It was supposed to symbolize the full collapse of these two brothers, where each of them was at their wits’ end in terms of their suffocation under their junk,” Lagasse explains.

Lagasse’s precise machine and hand stitching, along with well-thought-out construction, won him the 2023 Threads award to the Marist student exhibiting excellence in garment construction.

Lagasse says he is honored by the award and knows his grandmother is proud. A retired sewing factory worker with lots of home-sewing experience, she introduced him to sewing when he was in high school. They started with a button-front men’s dress shirt from a McCall’s pattern, and he was hooked.

Years later, his senior collection reflects his attention to detail and his commitment to sustainability through upcycling and the use of unwanted fabrics. There are clean-finished edges on the outside and inside of all the garments, plaid matching on the overcoat, surgeon’s cuffs on the coveralls, and much more.

Patrick Boylan, Lagasse’s mentor and a professor in Marist’s fashion program, says Lagasse was intentional about all his design and sewing choices. Lagasse took care in selecting fabrics, laying out his pattern pieces, and assembling the garments. He often consulted with Boylan as the collection developed.

Fabric trash to treasure

Lagasse had an enviable fabric source for much of his collection. He was given unwanted samples and yardage from a high-end designer’s Manhattan studio while he was interning there in 2022.

“Over 10 weeks, I hoarded fabric,” he admits. “By the end of the summer, I had this massive bin of all these different fabrics.”

The fabric for his wool trousers, for example, came from a huge blanket sent by a mill that “didn’t fit the designer’s aesthetic . . . so they gave it to me,” he says.

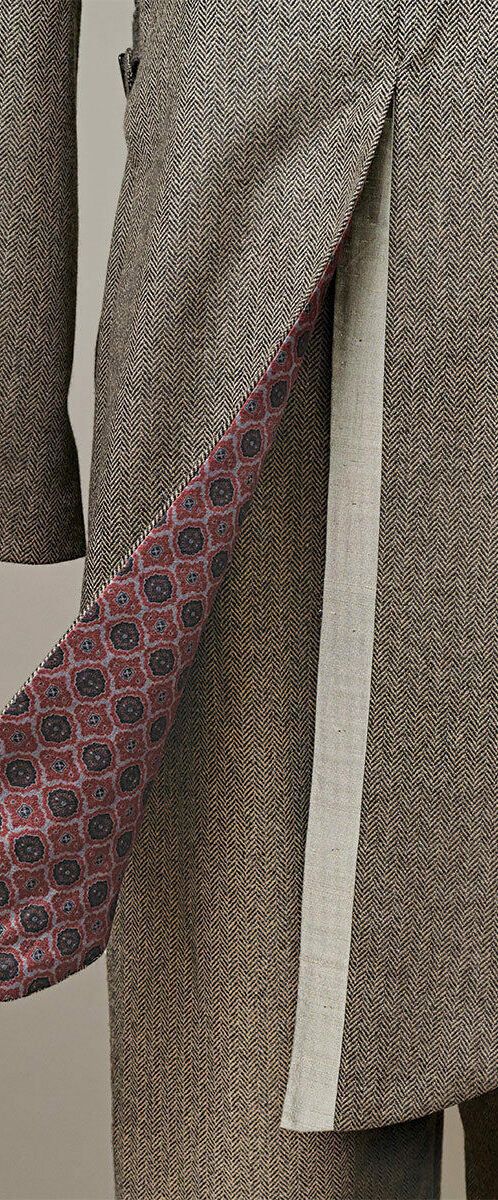

Other fabrics, including the wool herringbone for the coveralls and the plaid fabric in the overcoat, had been donated to Marist for the fashion students.

The gold silk shantung from which he made the boxer shorts and piping on the smoking robe came from Fabscrap in Brooklyn, New York, a nonprofit that collects and recycles or redistributes textile scraps.

Professor Boylan supplied silk taffeta remnants from his own stash to line the overcoat, and wool-blend foulard for lining the tails of the coveralls.

These odds and ends, whether vintage, donated, or unwanted pieces destined for the trash, made for an unusual fabric supply.

“Nothing about this collection is traditional in terms of the fabric,” Lagasse notes. So his approach to designing and sewing needed to be different.

“It was just a matter of trusting the process and doing it piece by piece as opposed to trying to do it the traditional way, where you design a collection and have the color story at the beginning.”

For this thoughtful student and planner who wanted every detail just right, that was his greatest challenge—letting the collection unfold as he sewed each garment.

|

|

Smoking robe and silk boxers

Lagasse was most proud of this look, especially as he watched the model wear it at Marist College’s Silver Needle Runway show earlier this year.

“It was so beautiful to see the hospital gown in the back flowing gracefully and the elegance of the escorial wool and the boxer shorts being able to fit precisely at the waist with the crease on the center of each leg,” Lagasse says. “I was superexcited just seeing [the model] walk with it and own the look. It brought it to life.”

Piping

Lagasse says that applying the contrast silk piping to the edges was a new experience for him. He achieved consistent results with the tried-and-true method of using a zipper foot.

Front facings from neckties

Lagasse created the robe’s patchwork facings from 10 blue silk neckties for which he had paid $2 apiece after digging them out of a bin at a Goodwill thrift store.

“I went home, took apart every single tie, and took my iron and pressed [each] open into the original piece,” he says. He then sewed the ties together to create a length of fabric from which he cut the front facings. Because all the ties were cut on the bias, nothing lay flat, he says, so he fused tricot to the back to stabilize the patchwork. He worked on small sections at a time in order to lay each as flat as possible before he fused them with ample heat.

|

Back facing challenges

Lagasse says he wanted to clean-finish the back facing on the unlined hospital gown but needed to include shoulder pads. The pads are typically concealed under lining. With his professor’s advice, he did both. He clean-finished the back facing and then hand-tacked the covered shoulder pads in two places, at the front facing and back facing.

Vintage style

To reflect the styles of the Collyer brothers’ era, Lagasse drafted a pattern for the silk boxer shorts. He borrowed details from the vintage styles he studied from the 1930s and ’40s: a curved waistband, pleats, three-button fly, and two button settings for waist adjustment in back.

|

|

|

|

Overcoat and union suit

Lagasse disassembled and reimagined a men’s dark green melton wool overcoat he had rescued from the trash heap.

Seaming

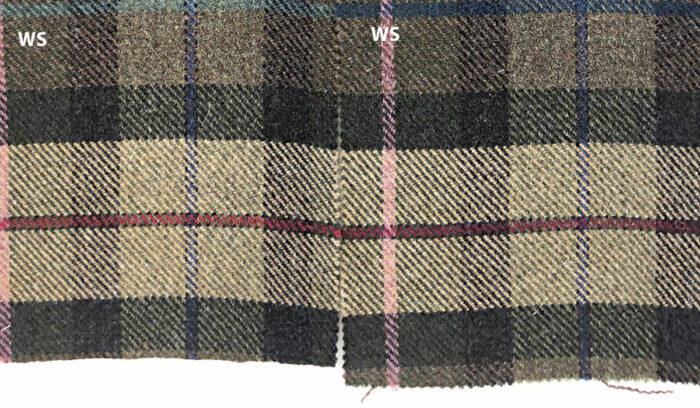

The designer cut a donated plaid fabric into strips to eliminate a wide tan stripe running through the yardage. He seamed the plaid strips using 3 ⁄ 4-inch-wide allowances to be sure the edges butted and stripes matched. He applied 2-inch-wide web interfacing to the plaid fabric when seaming it to the heavier melton. To match the plaids, a true challenge, he aligned and pinned at every stripe before machine-stitching.

“A few times, I got so frustrated I hand-slipstitched to make them line up,” he says.

Plaid matching at front

To align the seamed plaid fabric strips across the coat’s front, he laid out the unsewn coat sections. Then he chalk-marked the green melton wool from the center point of a few prominent stripes and matched the plaid sections to those markings before stitching.

|

Pieced knit union suit

Modeled after the long underwear worn by men in the Collyer brothers’ time, this backless one-piece garment is made of pieced knits that Lagasse had joined by fusing and then stitching together on his vintage Kenmore sewing machine.

“My Kenmore has a mending setting that does a really tight stitch to mend holes, he explains. “That is the stitch I used on the right side of the fabric to join these two blocks that I butted together.”

Lagasse sewed the union suit bib from some corduroy samples discarded by the designer’s studio during his internship.

|

|

|

|

|

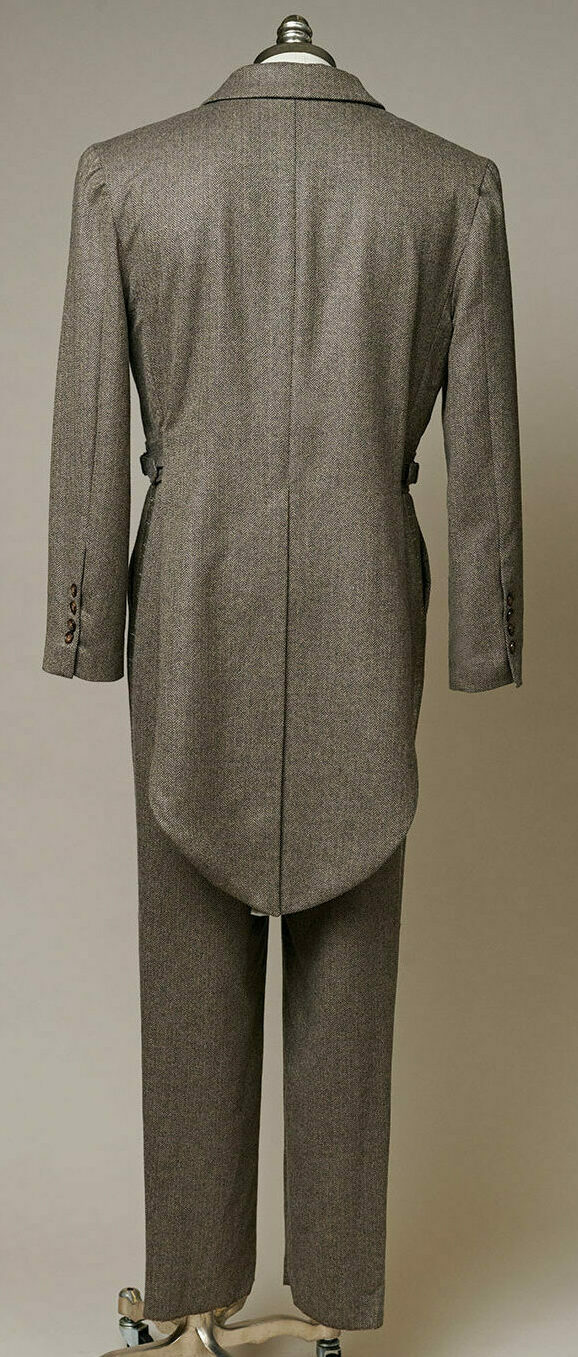

Dress shirt and trousers

Attention to detail paid off in this ensemble. Lagasse meticulously applied edge finishes on a sheer fabric that frays easily, and he added high-end menswear details to the hand-felted woolen trousers.

Fragile shirt fabric

To finish the edges of the delicate sheer voile shirt, Lagasse chose the purl function on a serger. He layered an organza facing under the front placket before serging, to add support and prevent the voile from shredding. The shirt hem features a coat-closing, or curved front edge, sometimes found in shirts of the Victorian period.

|

|

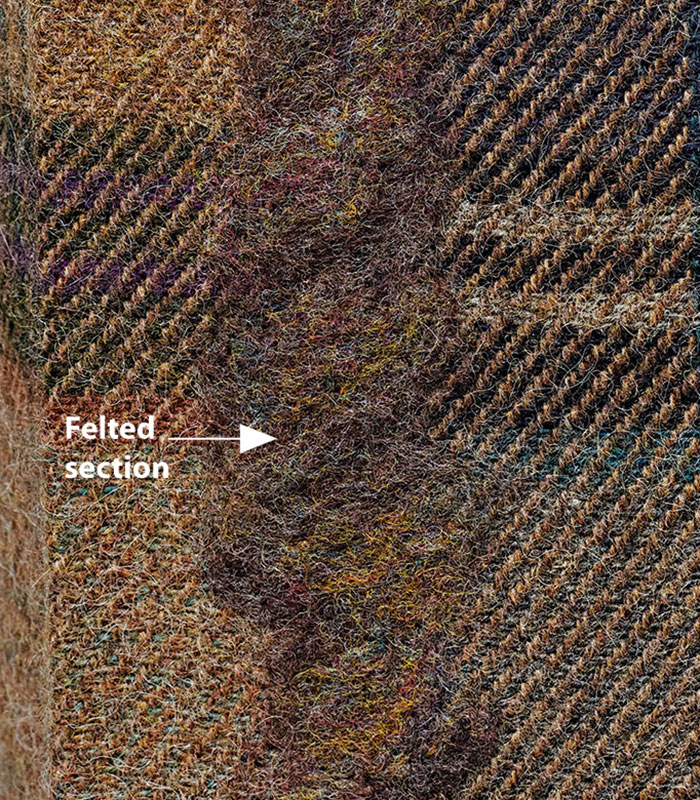

Fused and felted trousers

Lagasse included many details: fishtail waistband, suspender buttons, button-tab back welt pockets, and an adjustable center-back tab. The trouser fabric is unique: He created yardage by fusing and hand-felting plaid wool remnants. He walks through his fusing and felting process, below.

|

|

|

|

Fuse and felt your own yardage

The woolen trousers for my collection incorporated fabric samples destined for the trash. I cut, fused, and hand-felted the pieces together to create enough yardage. Supplies needed for the technique are minimal: wool fabric remnants or scraps, good-quality wool roving for the felting, fusible interfacing, felting needles, batting, scissors, and an iron. —Christopher Lagasse

1. Prep the materials

Cut the wool pieces on the grain and block them with steam. Be sure to cut clean, straight edges for easier alignment later. Then cut fusible interfacing strips 1 inch to 1 1 ⁄ 2 inches wide. I used Pellon fusible weft for my heavy wool pieces, but tricot also works.

2. With wrong sides up, lay two cut fabric pieces side by side on a pressing surface

Align plaids or prints as desired.

3. Place an interfacing strip, fusible side down, over the abutted area and fuse according to the product directions

Repeat until you have fused all the pieces to create a blanket of fabric large enough for the intended pattern. Turn right side up and notice the slight gap along the abutted fabric sections.

4. Cover your worksurface with multiple layers of batting

I piled up seven layers. With right sides up, lay the fused fabric pieces on top.

5. Use wool roving in a closely matching shade to hand-felt each abutted and fused seam

Do this by laying a small amount of roving over the gap. With a felting needle, prick the roving repeatedly in a stabbing motion to work it into the wool.

| Tips: Felt small sections at time. Lay the roving on a diagonal across the gap. Start pricking the roving from the center and work outward. Try mixing roving colors if you do not have an exact match or are felting multicolored fabric sections. |

6. Once felting is complete, pull the fabric away from the batting

Steam-press the fused and felted fabric’s right side with an up-and-down motion, and a press cloth if desired, to avoid flattening the felted area.

—Jeannine Clegg handles production work at Threads and has a deep appreciation for hand sewing.

Photos, except where noted: Mike Yamin.

For more photos and information, click on the “view PDF” button below:

From Threads #223

View PDF

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in