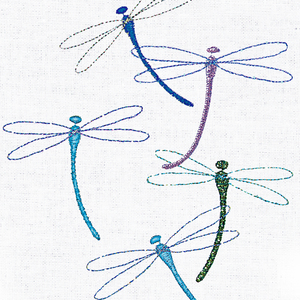

Small designs scattered over a garment can maximize the embroidered effect. These shapes are from the Dot Font design card by Cactus Punch.

Machine embroidery can be as easy as choosing a great design, plugging the design card into your machine, hooping your fabric, and pushing a button. But if your goal is to make beautiful garments with soft, supple embroidery, there’s much more you should know.

You can machine-embroider any fabric, including silks and soft wools. But producing exquisite embroidery that is well suited to the fabric, doesn’t pucker, or change the fabric’s drape, involves the interaction of all the following elements: a machine that’s well-tuned and set at the appropriate needle and bobbin tensions, a well-prepared and positioned design, the correct needle and thread for the job, and a good understanding of the fabric you’re embroidering so that it’s properly hooped and stabilized. I’ll examine these essentials, but I want to concentrate on how to choose designs and fabrics that are compatible with each other and tell you what to do when they’re not.

What makes a good embroidery design?

There’s more to a good design than subject matter and visual aesthetics. A well-digitized design is made up of a solid framework of stitches forming its outer edge, fill and satin stitches, and underlay stitches if necessary. The design should have a well-planned sewing sequence, with few jump stitches from one area to another, so there’s less thread-trimming to do. And it should be paired with a suitable fabric that displays it to its best advantage.

If you digitize your own designs or have them custom-digitized, you can take into consideration the characteristics of the fabric the design will be sewn on. But when you’re working with stock designs from independent design companies, from the Internet, or designs that come with your machine, it’s up to you to match the design with the fabric

Consider the fabric’s weight and weave

It’s important to understand that not every design should be used on every type of fabric, even with the proper stabilizer (see Are your fabric and design compatible?). A densely stitched design, for example, can put stress on certain fabrics, such as knits and lightweight, loosely woven fabrics, in some cases causing the weave to pull apart. Dense designs may simply be too stiff for a fluid fabric, but can be used successfully on stable, medium- to heavyweight woven fabrics.

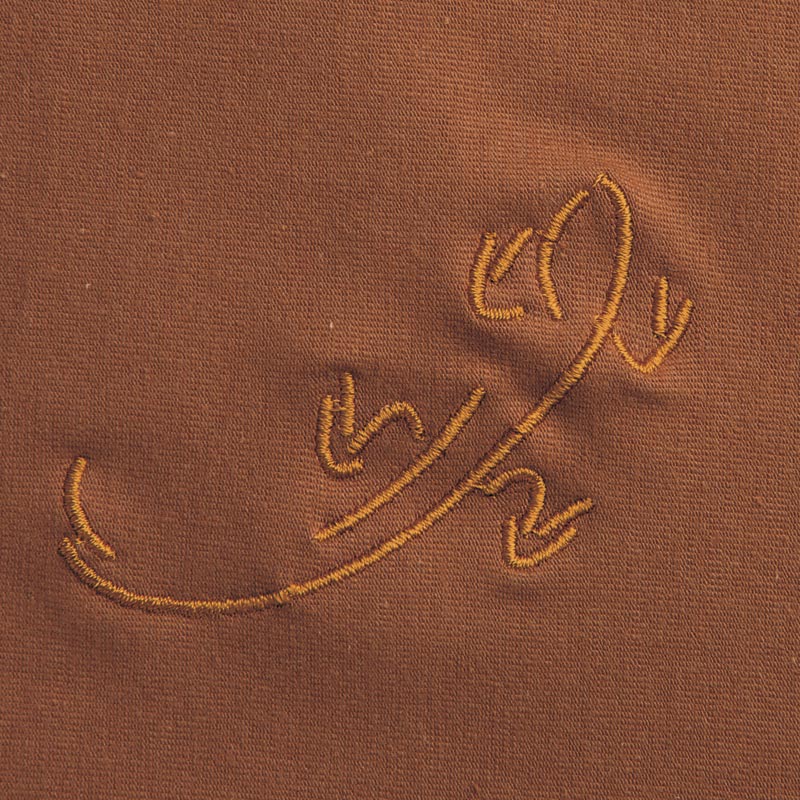

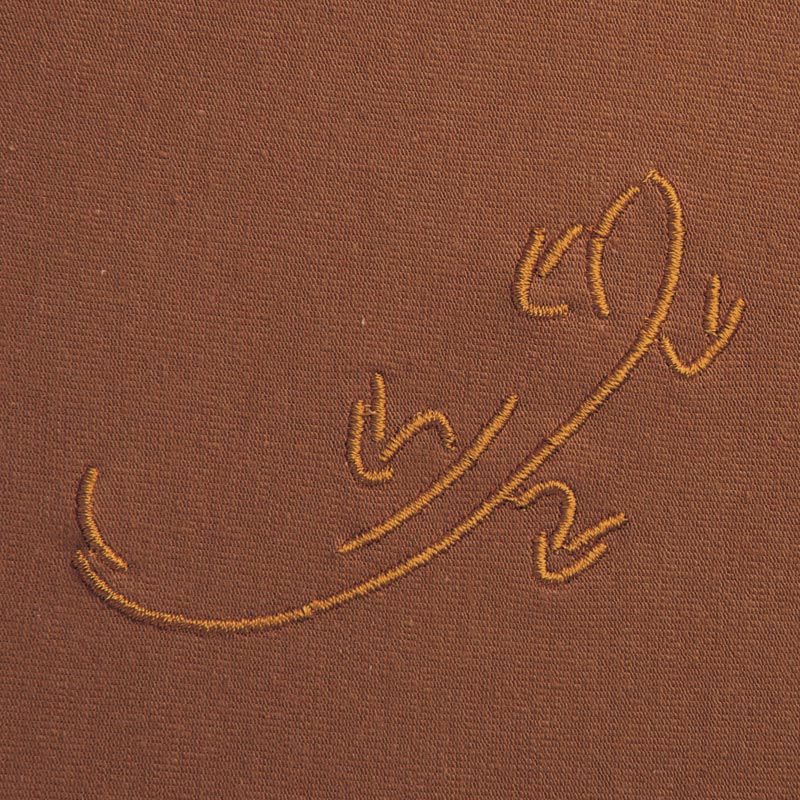

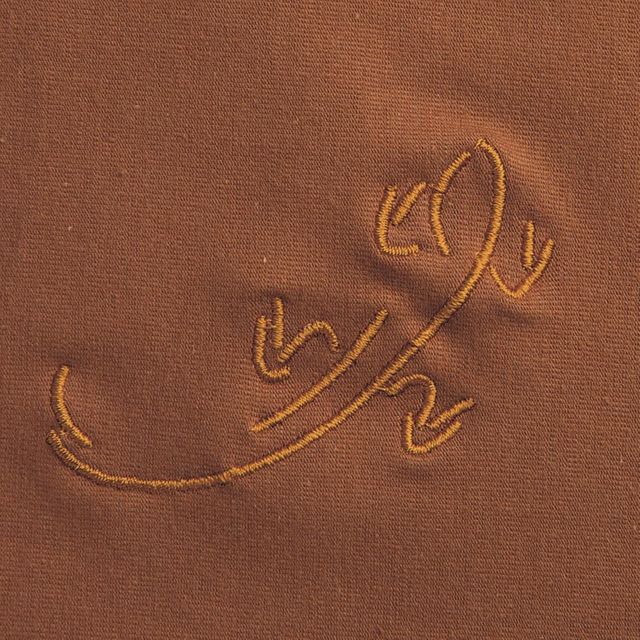

The threads of coarsely woven fabrics can deflect the machine needle while stitching, producing uneven edges.

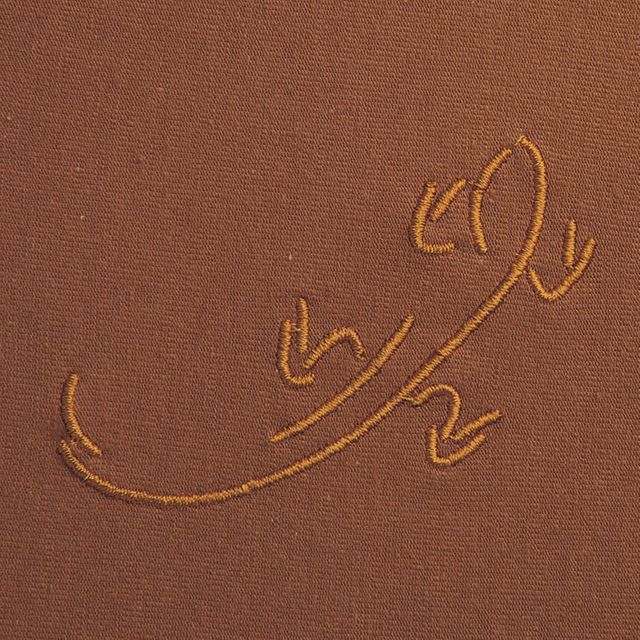

The same design stitches out cleanly on a more smoothly woven fabric.

A small, less densely stitched design may be wrong for a thick pile fabric, such as fleece or terry cloth, because its coverage may be inadequate, causing the design to be lost. This type of design works best on a smooth-surface, plain-weave fabric. And a design with substantial underlay stitches might be a plus on a deep pile fabric to keep the pile from poking through the stitches. Conversely, it may be too dense for a soft knit or drapey woven.

In addition to the fabric’s weight and weave, consider the fabric’s color and how you plan to use the fabric. Bold colors or patterns will probably obscure pastel embroidery, and a large, dense floral design on silk velvet, for instance, may work beautifully for a pillow cover but be awkwardly stiff on a long, fluid skirt. In some cases, you can alter the design to make it work; sometimes the best alternative is to choose a different design.

Are your fabric and design compatible?

For a successful marriage of fabric and design, consider carefully the fabric’s characteristics, its intended use, and the details of the design. Ask yourself the following questions, and always make test samples:

Will the design’s stitch density change the hand of the fabric? If so, is this a problem for your project?

How will the fabric’s color, weight, and texture influence the design?

Can you get better results by using a backing or topping?

Will the fabric and design work together if you simply change thread colors?

Can you alter the design to make it work, or is choosing a different design the best alternative?

Stabilizing the fabric: backings and toppings

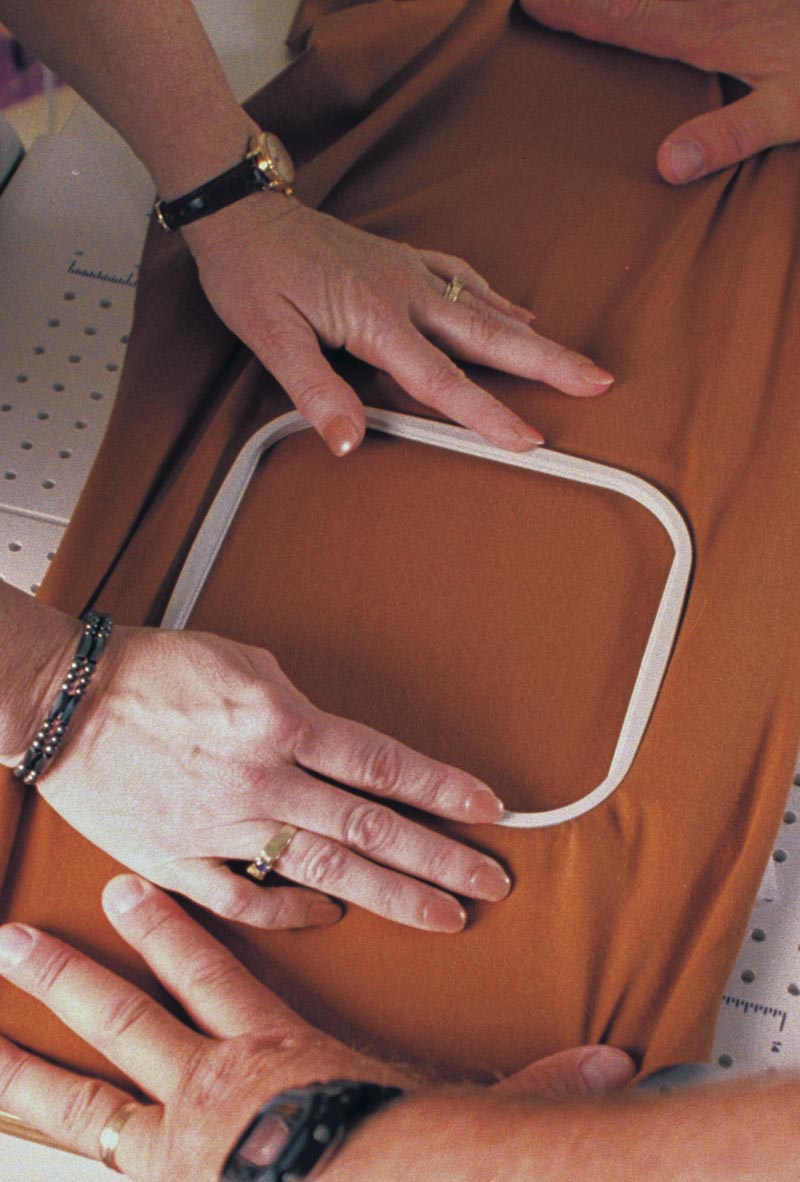

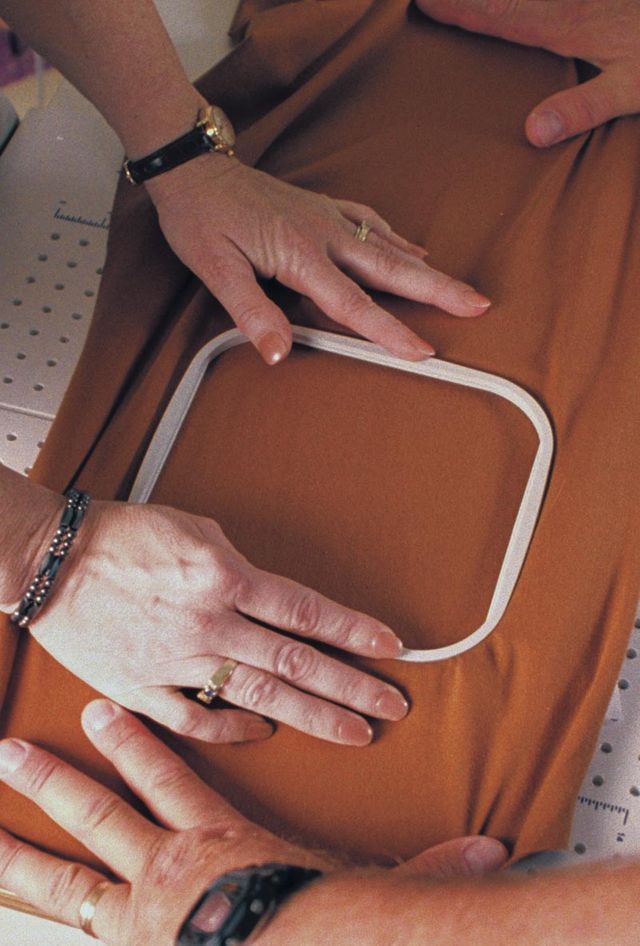

For stitching out a design, you need to hoop wovens and knits smoothly, with neutral tension, and no stretching. Velvet is an exception (I’ll discuss it in a moment). Lycra knits with four-way stretch, however, need to be stretched in the hoop (and backed with a cutaway stabilizer) in the same direction and amount they’ll stretch on the body when worn. Otherwise, the garment will not stretch on the body, causing undue stress on the design and fabric.

![]()

![]()

Different fabrics require different preparation. For Lycra knits, choose a design with a lot of open space. To hoop, stretch the knit as it’s worn on the body (top). The design will appear puckered when the fabric is relaxed (middle) but will stretch over the body when worn (bottom). Photos: Mary Ray.

Different fabrics require different preparation. For Lycra knits, choose a design with a lot of open space. To hoop, stretch the knit as it’s worn on the body (top). The design will appear puckered when the fabric is relaxed (middle) but will stretch over the body when worn (bottom). Photos: Mary Ray.

You may also need to stabilize the fabric by hooping it with a backing, sometimes called a stabilizer. Most embroidery-stitch designers recommend always using a backing, but very stable and tightly woven fabrics (such as organza or terry-cloth toweling) may not need backing at all, depending on the design.

Backings come in a variety of weights and types— cutaway, tearaway, heat-disintegrating, or water-soluble (see Backings and toppings). A backing should always be hooped beneath the fabric unless hooping will cause permanent marks, as it would on velvet or Ultrasuede. In that case, use a sticky backing in the hoop, and adhere the fabric to it. Or hoop a tearaway backing, and adhere the fabric with a temporary spray adhesive like Sulky’s KK2000.

I suggest using tearaway backings with woven fabrics and designs without a lot of fill areas. As a general rule, use cutaway backings with all knits and with wovens on which you’ll embroider a design with a large stitch count and large fill areas, especially if it has a running-stitch outline.

Toppings are not hooped but rather placed on top of the hooped fabric to compress or mat down nap or pile and to improve the resolution of stitches by keeping them from sinking into the fabric. Toppings also improve color coverage when the thread color contrasts greatly with that of the fabric. They can also add artistic effects or three-dimensional and raised effects. Toppings are torn away around the completed design.

Hooping a backing beneath the fabric and/or laying a topping over the hooped fabric can help stabilize and prepare the fabric for embroidery. Select the backing or topping to coordinate with the fabric or design used.

Common backings

* Nonwoven tearaways (Sulky Stiffy, Tear-Easy, Totally Stable); can use on most fabrics

* Nonwoven and woven cutaways (Sulky Soft ‘n Sheer, Cut-Away Plus); use on knits and lightweight wovens

* Sticky backings (Sulky Sticky; Stick-It-All from Hoop-It-All); use on fabrics that cannot be hooped, such as velvet, Ultrasuede, and leather

* Meltaways, burnaways, washaways (Solvy; Sulky Heat-Away; Stick-dsolv from Hoop-It-All); use on sheer and lightweight fabrics and for cutwork designs

Common toppings

* Water-soluble films (Solvy, Stick-dsolv); use on textured knits and on top of other stitching

* CoverUp from Hoop-It-All (available in colors); use on fabrics with high-contrast colors

* Lamé, or mylar; use to create shimmering effect through embroidery.

A word about stock designs

Stock designs are those available from your machine manufacturer or from independent design companies and formatted for your machine. You can also find an abundance of stock designs available free on the Internet. Professional design companies have experienced, knowledgeable staffs who spend a lot of time creating and testing their designs so you’ll get excellent results when they’re used properly, but this may not always be the case with free designs.

All stock designs are created for what I call average fabric conditions. This means the fabric on which the design works best is a solid-color broadcloth that’s hooped on-grain and is light or neutral in color. If you stitch out stock designs on fabrics that vary from this norm, you may run into some problems, even with perfectly good designs, and you’ll need to make some adjustments to your fabric to get good results. I’ll talk about that in a moment, but first let’s look at how to determine whether a design will work well for your fabric. The best way is to do a test run on the actual fabric or one that’s very similar. Watch as the design stitches out to observe how the underlay is produced, where the jumps are, and the direction of the fill stitching.

If you see that the design is not stitching out to meet your expectations, what do you do? You could edit the design to suit the situation, if your software’s features and your ability with the programs permit. Or you could contact the company from which you purchased the design and have it edited (for a fee) or have a new design custom-digitized. But keep in mind, if you have a design digitized for a specific fabric, it may not work well on other fabrics.

Another solution to this problem is to make your fabric as “average” as possible by using backings and toppings so the fabric is compatible with the stock design. Below are common problems embroiderers encounter; some are solved by and some are caused by using or misusing backings and toppings.

Troubleshooting: puckering and distortion

The most frequent complaints I hear from machine embroiderers involve puckering, poor fabric coverage or poor registration. Puckering and distortion can occur if a design is too dense for the fabric. For example, if a design has lots of full-coverage fill areas with layers of blended stitches on top, it may not be the best choice for knits or lightweight, drapey fabrics. Knits stretch horizontally and designs with vertical fill will push the knit along its horizontal axis and cause the knit to open up, creating wavy, puckered embroidery. Most puckering problems can be eliminated by adding a backing. But do you really want to take a fabric with a soft, drapey hand and create a stiff, poster-board effect on part of it? The design in question may be perfectly suitable for more stable fabric, but for a lightweight fabric or one with a loose, unstable weave, use a design with fewer fill and satin stitches.

In addition to choosing a design that’s too dense for your fabric’s weight and/or weave, there are other reasons your embroidery might pucker: Fabric that’s stretched too tightly when hooped will relax when unhooped. Overly tight machine tensions (see Needles, threads, and tension) can also cause puckering. To test your tension balance, sew a 1-in.-tall block letter H, using a bright color in the needle and white in the bobbin. Check the wrong side after stitching. If you don’t see any bobbin thread, your bobbin is too tight or your top thread is too loose, or both. If you see a bobbin thread column about one-third the width of your satin-stitch column, your tensions are balanced. But before you rush to adjust your tensions (some machines have automatic tensions), check the threading. Because rayon thread is slippery, it can jump out of the take-up lever, causing tension problems. Therefore rethread the upper thread path, and check the bobbin to be sure it’s threaded correctly, too.

Start with a new needle that’s the right type and size for your fabric and thread. A needle that’s wrong or damaged can cause excessive thread shredding or fabric damage.

If you vary the thread from 40-weight embroidery thread, test the design before stitching it out on your garment.

Remember, too, that thread breaks may be caused by old thread (store in a dust-free container away from strong light and heat sources) or overly tight tension, which may still appear balanced.

Stitches that are too tight can stretch the thread and distort the fabric and design. Know your machine’s tension settings: Some machines control needle tension automatically; others require a dial setting.

Poor fabric coverage

Poor fabric coverage may be the result of the fabric color or texture, thread choice, enlarging the design, or even personal preference. For example, a stock design with creamy yellow daffodils composed of longer satin stitches will probably not work well on plush forest-green terry-cloth toweling unless it is specifically digitized for terry cloth. If this is the case, the design would have a grid of underlay stitches to mat down the terry loops and maybe some zigzag underlay to keep the top satin stitches lofty and prevent the terry cloth’s color from peeking through and the stitches from being lost in the pile.

To counteract poor coverage, consider using a topping like CoverUp, which comes in colors. The correct color can neutralize the effects of colored or printed fabrics and hold the pile of a fabric in check all at once.

Enlarging designs on some embroidery systems lengthens the stitches and increases the spacing between them (lowering the stitch density). These designs will not cover fabric as well as their unscaled counterparts. If your customizing software only elongates the stitches and spreads out the rows, try using gold lamé as a topping. The spaces created from lengthening the stitches will have the shimmering lamé peeking through, and you may even create a more interesting effect than the original design.

Personal preference also influences what you think about fabric coverage. Too many embroiderers expect total coverage of any fabric, regardless of thread-color choices. This results in stiff embroidery, which professional embroiderers and digitizers consider to be of poor quality— and which will probably result in other problems, such as puckering, thread breaks, or even fabric damage.

Misalignment problems

Poor registration (gapping or misaligned outlines) can result from using a tearaway backing with a design that has large fill areas. These designs can break down a tearaway and compromise stability before the outline has been completely sewn. Use a cutaway backing alone or adhered with embroidery spray adhesive to remedy the problem.

Overly tight tensions can also cause poor registration. In this case, you may need to loosen both your bobbin and upper thread tensions to correct it. The threads of a coarsely woven fabric may cause what might appear to be poor registration: The fabric fibers can deflect the needle to one side of the fabric threads, causing uneven edges. For clean-edged results, choose a stable, smooth-finish fabric.

With careful use of high-quality designs and thoughtful fabric choices, you can ensure good results and have more fun at your embroidery machine.

Article written by Lindee Goodall, Threads #86, pp. 36-41.

Lindee Goodall of Tucson, Arizona, is the president of Cactus Punch Designs and teaches classes on machine embroidery at shows around the country.

Photos except where noted: Sloan Howard

Another great refresher....thanks!