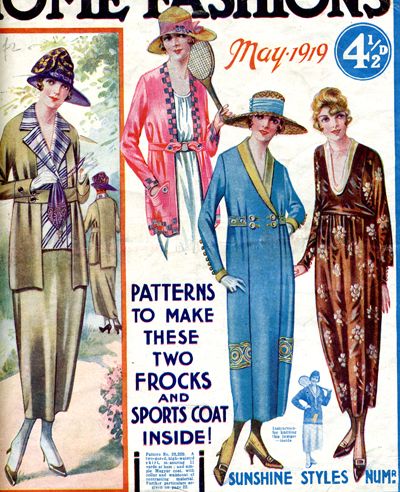

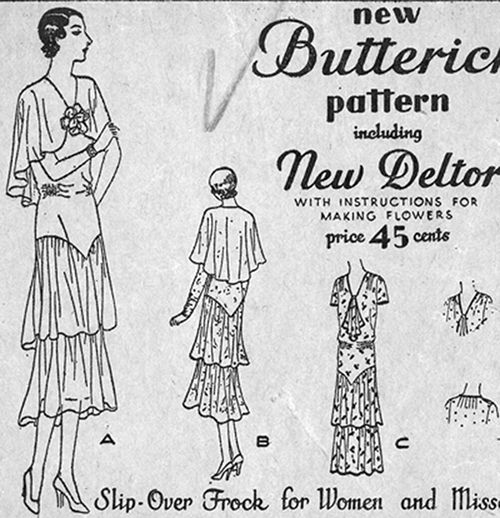

Butterick 3168, "Slip-over frock for women and misses," 1930.

JOY SPANABEL EMERY

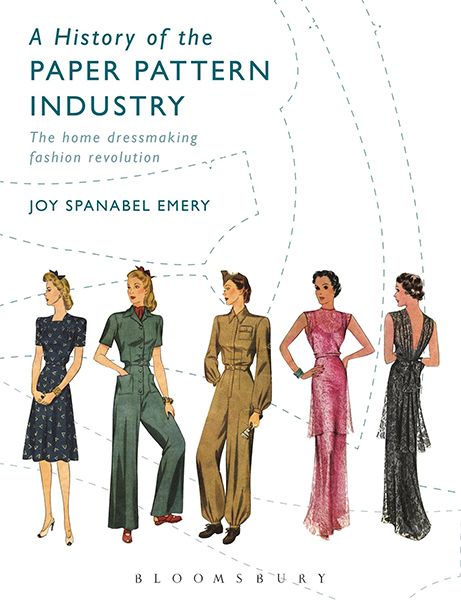

Joy is a professor emerita of theater at the University of Rhode Island. She has collected over 100 years of knowledge about the complex history of the companies that built the North American home sewing pattern industry and the technological advances that made it all possible. Joy is the curator of the university’s Commercial Pattern Archive, considered the largest collection of sewing patterns in the world. She recently published A History of the Paper Pattern Inudsry: The home dressmaking fashion revolution, a book about the evolution of the paper pattern industry and its innovations in manufacturing and marketing. You can read more about her book on the original blog post.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOY

Threads magazine (TH): What is the purpose of the Commercial Pattern Archive? Why was it created?

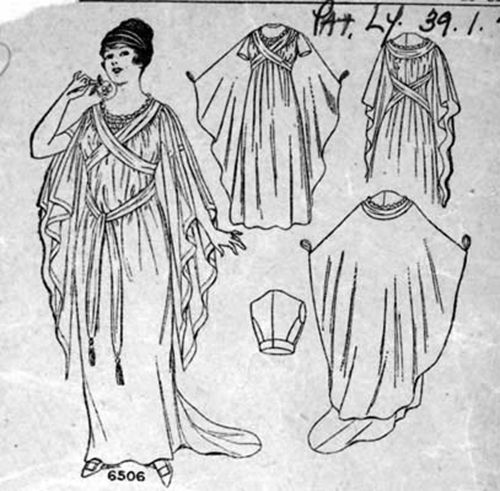

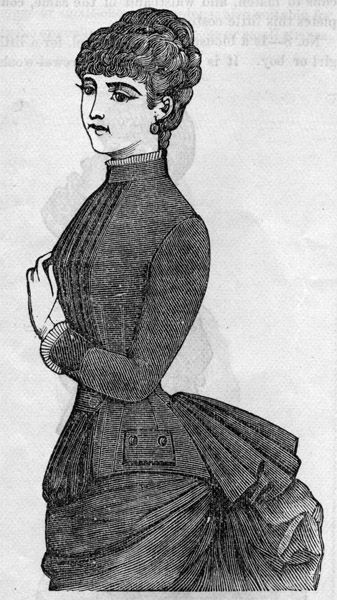

Joy Emery (JE): The purpose is to preserve these very rare documents that are the history of fashion, particularly everyday fashion from the 1840s. People always save the special garments; that’s what ends up in museums and in your special closet, but these patterns represent everyday wear, and they represent the broad spectrum of fashion for all walks of life. The other nice thing about the patterns is that the commercial ones, particularly Butterick and Simplicity, we have been able to pull together information so that we can accurately date when the pattern was issued. We can use the patterns and those fashions to date garments that are almost impossible to date otherwise.

TH: How many patterns are in the archive?

JE: In the database, there are almost 58,000 records. In the archive here, physically, we have about 48,000 to 49,000.

TH: How can they be accessed for study?

JE: The online database allows subscribers to search all kinds of criteria and you get the image of the pattern’s fashion design. We also scan the pattern schematic, so you can see the pattern shapes and get a sense of layout. Those can be printed out, and they can be enlarged for whatever size is needed. I can guarantee that even with all the patterns we do have, we won’t have the specific size someone wants. Personally, I use the schematics as a basis for draping a new pattern, because it gives all the necessary information like seamlines and grainlines.

The stuff that we’re scanning is only for research and personal use, not for resale. You have to pay to access the database, available by subscription, and all funds go to the URI foundation. We use those funds to pay students to process patterns and get them entered in the database, then get them scanned and filed away so we can find them again.

TH: What is the oldest pattern date in the collection?

JE: 1847

TH: And what’s the cut-off date for considering a pattern ‘vintage’ for the collection’s purposes?

JE: Depends on whom you’re talking to. Betty Williams, who was the pioneer in all this, she had a cut-off date of 1959. I started working with her in the late 1970s-early 1980s, and realized that my students didn’t know what the 1960s looked like. I thought we needed to expand the cut-off date, because time keeps moving on. We have not really put a cut-off date on the archive yet. We may have to, because we’re running out of space. But the idea is to have this here for future generations.

TH: Why is it important to conserve commercial sewing patterns?

JE: The pattern tissues are in incredible shape. They’re not disintegrating. Some of the envelopes and instruction sheets are, but not the patterns. We can’t scan the full-scale pattern. The database and images are wonderful things, and a lot of stuff was preserved on microfiche and film, and it’s vanishing before our eyes, and in creating microfiche and film the originals were destroyed, and I can’t bring myself to do that. But I also know that film is a vulnerable medium, and we don’t know what the lifespan really is. By preserving the originals, they’re going to be there.

TH: What can they tell us about the past, about our history, our forebears, about technology and manufacturing processes?

JE: They can tell us a lot about all that. You can document all the fabric stuff: When did the zipper first come in, for example. Then there’s terminology. We use the name of a garment, but it keeps changing. If you’re doing research and you come across these weird old terms and want to know what they are, with our database you can search that word and see what the patterns tell you about the garments, and you can also trace the changes.

For example, a redingote; we have a lot of them. It’s like a coatdress. It’s fascinating to see how they change over the span of time. I love the masquerade costume patterns. You can trace the changes from age to age. I like to trace women’s sportswear, but also patterns for men and children. The men’s things are mostly soft, not that tailored. But in the Seventies you have the leisure suits, and we also recently got a pattern for a zoot suit.

The pattern archive is about sewing, it’s about fashion, but it’s also about history across the board: women’s history, business history, and fashion history. The logos on the patterns show design and marketing history. You can see and trace the various influences.

TH: How do URI students and others use the CoPA? For what purpose?

JE: It’s international. We have subscriptions from Australia, Austria, Israel, Germany, and Britain; there are a lot of university libraries. It’s a very good resource for libraries to use. They get a group subscription. There are also a large number of individuals. Some of them are part of various sewing networks, and they’re interested in it to use the patterns to make things for themselves. A lot are vintage pattern dealers who use the database to help date their patterns.

I have a researcher coming in next month from Japan doing a study on mid-19th century women’s garments. I’ve also had people from Mystic, Connecticut, for example, come in and trace patterns. We do allow that to researchers. And then they can use that to create garments for docents at museums, etc. Museums sometimes come in: The Boston Museum of Fine Arts was looking for stuff from the 1960s, because they had to make garments to augment what they were showing in the exhibit. Theater folks come and use it for research because it’s everyday wear, which is essential for any film or theatrical production-TV, stage, whatever.

TH: Is the archive being added to, or is it fairly static at this point?

JE: Oh yes . . . I have a big drawer full right now I’m supposed to be adding. The Fashion Institute of Technology decided they weren’t doing anything with their pattern collection, and they decided to send it here. So we just got their entire collection, and a few years ago we got the Butterick archives. They sent us all their patterns and many of their periodicals. Our archive has fashion magazines, counter catalogs, tailoring books, and journals, especially men’s tailoring journals.

I started this project when I retired because I wanted something to do (in 2000), and I’m still at it. It’s never-ending, and that’s what I wanted.

TH: Why did you write your recently published book, A History of the Paper Pattern Industry?

JE: Betty Williams was the walking encyclopedia on all of this. She could rattle off all kinds of information about the pattern companies. The history of the pattern companies, watching that business and the marketing techniques they used, it’s really fascinating. But nowhere was it recorded. There are bits and pieces here and there, but it hadn’t been pulled together. People were after me for a while to get it all recorded. So I finally decided to do it and get it down and use it as a leaping-off point because there’s so much more that can be done.

Current pattern companies still use some of the same marketing methods today as they did in the early 1900s. And watching them weather the economic ups and downs is fascinating. And this is another way CoPA fulfills a need: When I was working on the book and trying to get some information on Simplicity, they tried to be helpful, but they don’t know anything about their history because it’s all been lost. Even Butterick, which was the one company that maintained an archive up until the early 2000s, couldn’t afford to keep even a part-time archivist, and they were downsizing space-wise. They didn’t want to lose that information, so they sent it to us.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Do you think it’s beneficial to have an archive available for research? Share your thoughts with us by commenting below.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in