Improve your sewing by marking things that matter

by Barbara Emodi

from Threads #79, pp. 38-40

Besides all the surprising things that I’ve inevitably learned from the ingenuity and talent of my students, one of the most interesting aspects of working with lots of sewers is how one begins to see that almost everybody (myself included), no matter how skillful or experienced, has a few blind spots, or areas where they could improve their results. Of course, blind spots will vary from sewer to sewer, but they tend to occur in areas you think you have down cold. So, I suggest reading through the following wide-ranging list of potential pitfalls (developed in the course of conversations with my students and other teachers, in our relentless pursuit of ever-more-satisfying sewing projects) with as open a mind as possible. May it prove as useful to you as it has to us!

1. Mark the things that matter

It’s important to always mark center front. Thread-trace lines that need to be seen on the right side (pocket placement, roll lines). Color-code your markings-how can you tell a large dot from a small dot if you’ve tailor-tacked them in the same thread color? This will save time, not waste it. How often have you pulled out the pattern pieces to double-check a marking?

2. Establish priorities when choosing a pattern size

Few of us are one size all over, so be sure to select a pattern size to best fit the part of your body that will carry the weight of the garment. When buying a pattern for an upper-body garment (jacket, dress, shirt, blouse, or coat), choose the size that fits your shoulders and neckline. When buying a lower-body pattern (pants or skirt), choose a size that fits your waist and upper hip. Shoulders/necklines and waists/upper hips on patterns are very difficult to alter, so it’s easiest to start off with the closest possible fit right from the pattern envelope.

When you choose tops, use your chest measurement (above the bust, as high as possible under your arms, and over your shoulder blades-don’t worry if the tape isn’t perfectly horizontal at all points) and alter for the bust if there’s more than a 2-in. difference between your chest and bust measurements. It’s always much easier to make a pattern larger than smaller.

![]()

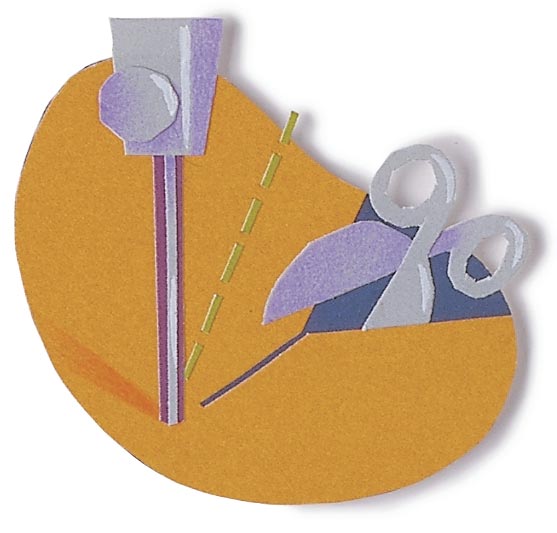

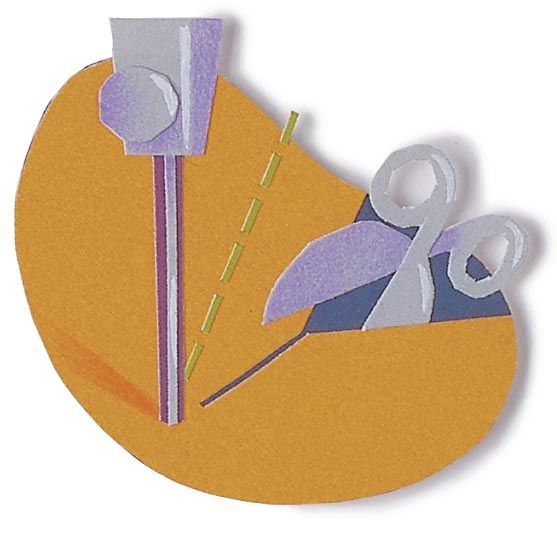

3. Work with, not against, your sewing machine

Police yourself for bad fabric-handling habits. Look for evidence. Do you have nicks across the top of your bobbin case? These can be caused by broken needles, sewing over pins, or the needle striking the bobbin case in a machine whose timing (the relationship between the needle’s downward stroke and the rotation of the bobbin hook) needs adjusting. Breaking your needle on a pin at high speed can be enough to knock a machine’s timing off.

Do you have scratches on your throat plate running out backward from the needle opening? This is caused when the needle is bent backward, usually by sewers who use their hands to overzealously “help” the fabric feed through the machine. This practice causes deadly wear and tear on machines.

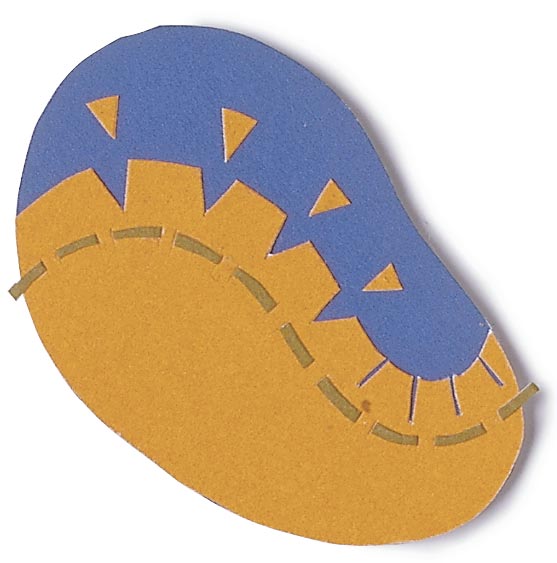

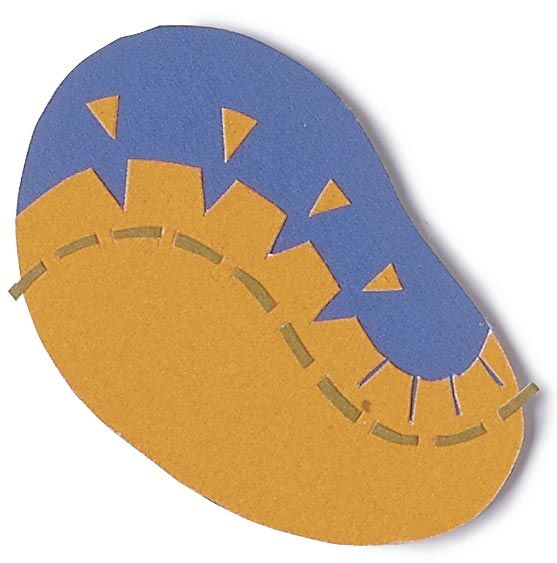

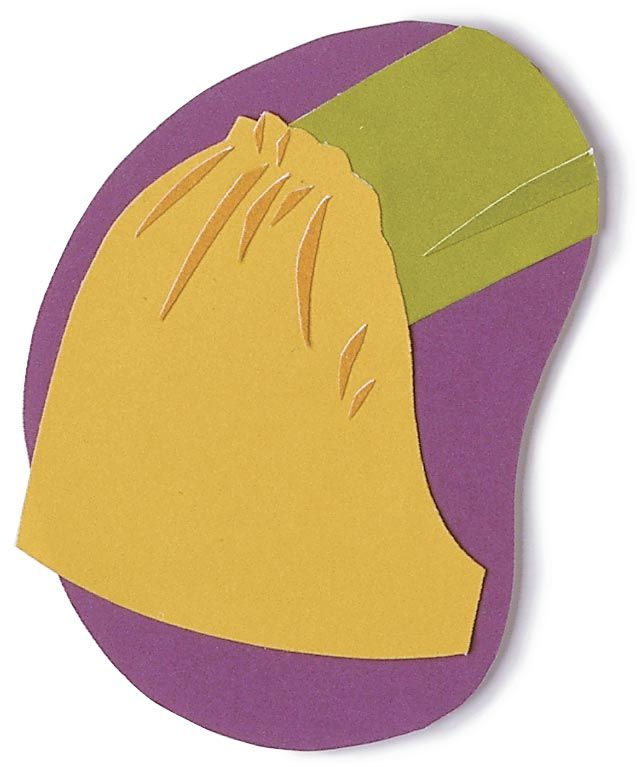

4. Eliminate internal bulk

Understand when to simply clip a seam allowance (when a curved seam needs to be straightened, or when turning an inside curve or corner) and when to actually remove fabric from the seam allowances with a notch (when turning an outside curve or corner). Grade seam allowances bravely; don’t let your fear of fraying make your sewing lumpy. You can trim as close as 1/8 in. to the seamline without fear, so get a ruler and remind yourself what 1/8 in. looks like. Whenever possible, use a flat finish (for example, serging or zigzagging, then stitching in the ditch to finish a waistband) rather than folding under and slipstitching.![]()

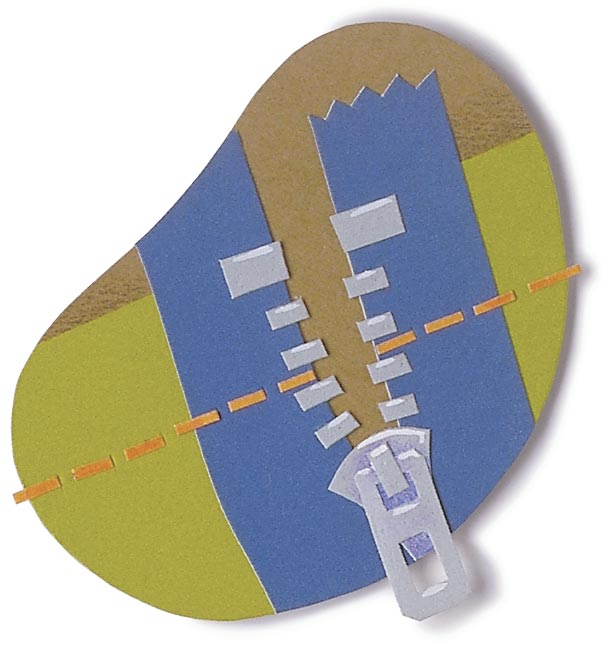

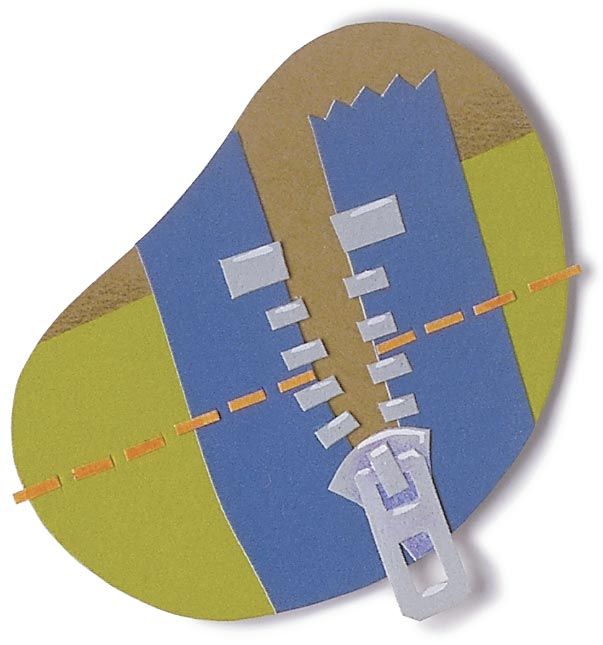

5. Buy longer zippers

A good choice is at least 1 in. longer than the pattern suggests. Stitch both waistbands and neck facings right across the top of the zipper tape (use nylon zippers), cutting off the excess at the top. This eliminates that annoying gap between the top of a zipper and the waistband (many fly-front pants deal with the problem this way, so why not skirts?), as well as the need to sew a hook and eye to the top of a dress zipper.

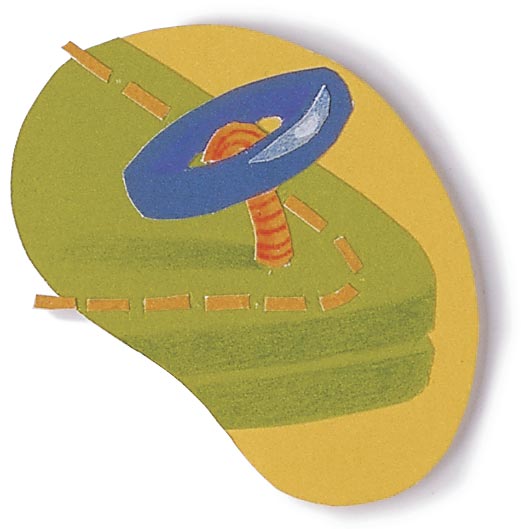

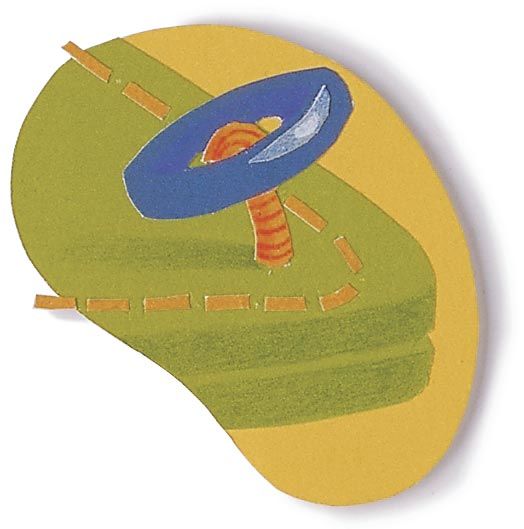

6. Give gadgets a chance

Keep up with new notions and accessory feet. A job you hate may turn out to be a snap with the right tool. Learn how to use a loop turner, a bias-tape maker, a narrow hemmer, and a flat-felling foot. But don’t stop there; keep on learning.![]()

7. Respect “turn of cloth”

Folded fabric layers take up room, so press completed collars before attaching them to a garment, carefully rolling the collar seam to the underside. Expect the undercollar to protrude slightly along the neck edge. Trim away this excess fabric and baste the collar’s raw edges together. Also, to allow for fabric thickness when attaching buttons, make sure the shank (thread, plastic, or metal) is as long as the fabric layers are thick.

8. Use traditional pressing tools to supplement the performance of your iron

The iron is only part of the equation, and modern irons are indiscriminate and excessive steamers. Dab or spritz water on small or hard-to-press areas. Extend the capacity of your iron with a clapper and a point presser made from hardwood (don’t use pine; it’s too soft and resinous). Wood absorbs extra heat and moisture and returns it to the fabric so that you can press longer without scorching, plus it provides the hard surface you need to make sharp creases or open seams fully.

9. Consider an underlining

Adding an underlining can supplement or change the weight, hand, or drape of a garment fabric. Duplicate the pattern piece that needs help in a second fabric, and work with the fashion fabric and underlining as one. Underline, for example, to support a limp fabric with a firm fabric, or a loosely woven fabric with an opaque one. Always treat the underlining fabric as the secondary fabric; don’t let it outweigh or dominate the primary fabric.

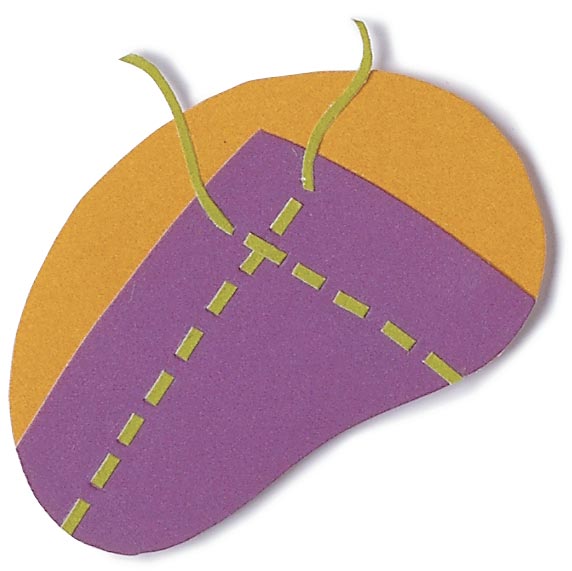

10. Eliminate back-neck facings in garments with a collar

Substitute a serged or bound neck edge; you’ll never miss the facing, and you won’t have to struggle to make it lie flat.![]()

11. Cross seams, don’t pivot, whenever possible, at the junction of two seamlines

Pivoting can cause twisting and distortion of the grain, which often creates a bubble at the point of an in-set, for example, that no amount of pressing will eliminate. For the same reason, always stitch both seams away from, rather than toward, the point of intersection.

12. Keep in mind that shoulders move

If your garment has shoulder pads, you’ll need to stitch some mobility into the points of the shoulder pads. Working from the right side, hand-sew a small, invisible backstitch in the ditch of the shoulder seams to attach shoulder pads from sleeve to neck, catching just the pad cover, and use small swing tacks on the inside to anchor the points of the pads to the armhole seam allowances.![]()

13. Prepare sleeves to fit armholes

Measure the armhole and shape the sleeve cap to fit; don’t try to stitch the gathered sleeve in place and then press it into shape. Ease and gather the sleeve seam until the measurements of the sleeve and armhole match. Then hang the sleeve cap over a tailor’s ham or the small end of an ironing board and steam-press it until it’s smooth, shaped, and all puckers have been eliminated. Only then, pin and stitch the sleeve into the garment.

14 Learn the difference between topstitching and edgestitching. The side of your presser foot isn’t always the best distance to stitch away from an edge. Topstitching defines an edge or attaches a detail with stitches more than 1/8 in. or so from the edge, and edgestitching (stitching less than 1/8 in. from the edge) often does this job better. Keep your topstitching, like all other elements, in proportion to the scale of the garment and fabric. Consider placing topstitching a distance from the edge of the fabric that reflects the fabric’s own body and thickness. Thin, hard fabrics like fine gabardine should be edgestitched close, perhaps 1/16 in. from the edge. A lofty mohair coating, by contrast, would probably look better topstitched 1/4 in. or more from the garment edges.

15. Don’t use a standard hem measurement

A good hem is one that hangs nicely, which in different fabrics means different hem widths. As a rule, the wider the skirt, the narrower the hem-and vice versa.

16. Clip to the stitch, don’t stitch to the clip

Many patterns (especially those with V necks) tell us to clip and then stitch to the end of the clip. This can be very difficult when the fabric frays easily, or when we lose sight of the end of the clip under the presser foot. It’s much easier to mark the point to be clipped to, stitch to this point, stop in the needle-down position, lift the presser foot, and then carefully clip to the stitch. Then lower the presser foot and complete the seam.

17. Interfacing is a discretionary material!

Don’t just follow the pattern; treat the suggestions in your pattern or guide book as starting points and use your own hands and eyes to tell you what areas in this garment need support or body. Examine your own clothes (actually open the linings!) to discover how ready-to-wear uses interfacing to get results you like-it’s got to be either the fabric or the interfacing, or both. And don’t just buy a basic interfacing or two and use them everywhere; start a collection and test each one.

Also, don’t be afraid to layer a favorite interfacing until you get the effect you want, or to use more than one type of interfacing in the same garment. In fact, it’s sensible to use a heavier interfacing in a lapel, a lighter-weight one in a jacket front, and a medium-weight one in a hem, even if it isn’t suggested in the pattern. That’s how it’s done in ready-to-wear.

18. Deal with ambitious seams in sections

For example, when sewing a seam that will involve matching up crossing seams or details (two sides of a waistline, yokes, piping, and so on), stitch only a few inches at the point of intersection. Stop, check to see whether the cross seams line up, adjust if necessary, and then complete the seam.![]()

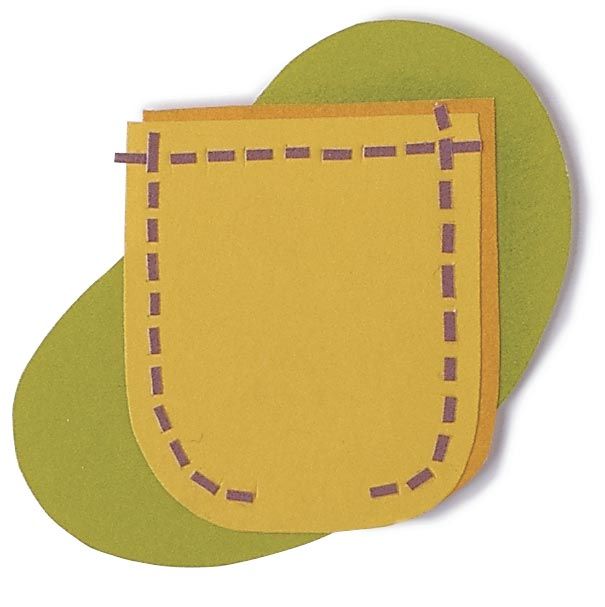

19. It’s easier to stitch a curved edge than to press a curve

Forget about using those metal corner-shaping templates (unless you can find a way to use them without burning your fingers) or turning up along a stitched line. Instead, simply line and turn all curved pockets, flaps, and similar details. It’s faster, simpler, and cleaner.

20. Sewing is, above all, a sensual and emotional experience

Don’t even begin a project if you don’t love the color and enjoy the feel of the fabric. Fit may be flawless, design stunning, workmanship impeccable, but if the fabric doesn’t appeal to the senses, you’ll never wear it.

Drawings: Karen Meyer

I thought this was well thought out & the last comment is so true so I recently donated all my bits to a migrant learn to sew group & its interesting to see my pieces of fabric walking around the streets all made up & someone has fallen in love with them. Some of these fabrics I have kept for many years carting them around the globe then thinking what made me buy that its not me

I agree. #20 was the very first thing Mom taught me when I was nine and just starting to learn to sew.

As a sewer of 40+ years, I recognize good advice and there's a lot of it here.

Thanks.

This helped alot with the placement and how to do the pockets in the seam of a ready made dress.

The diagram that shows when to clip a slit and when to clip a V is the wrong way around.

On an external curve, clipping a slit is correct. There is less fabric on the outer edge than on the seam, so the curve will spread these slits apart to allow the outer perimeter to be larger than the inner one. You don't need to clip a V.

On an internal curve, the perimeter at the outer edge is larger than at the seam. It needs to squash up into a smaller space so to you need to clip V notches to prevent the fabric from overlapping and being lumpy. The Vs will just look like slits around the curve once it's clipped.

You have Vs on the external and slits on the internal - please correct the diagram: 79-improve-your-sewing-04.jpg - move the V shaped bits above the internal curve.

About the diagram for #4, when it is turned, would not the outside curve then be an inside curve, and vice versa? Or am I just seeing it wrong?

I'm having a difficult time understanding how #13 would work. If you're pressing it first, aren't you just pressing it back to its original size, before it's been gathered?

I believe tip wants you to gather the sleeve to armhole size, then press over a ham or small ironing board. Then you sew into the armhole.

Thank you for the thoughtful and helpful article.

I believe tip wants you to gather the sleeve to armhole size, then press over a ham or small ironing board. Then you sew into the armhole.